“War is good, it reshuffles the cards”: Qiu Zhenhai’s taxi ride

Posted: April 20, 2014 Filed under: Academic debates, China-Japan, Diaoyu, State media | Tags: anti-Japanese protest, Chinese foreign policy, Chinese internet, Chinese nationalism, Diaoyu Islands, 邱震海, Li Weizhi, online nationalism, Qiu Zhenhai, south china sea 2 CommentsThe introduction to Phoenix TV host and international affairs commentator Qiu Zhenhai’s book, excerpted in Southern Weekend a couple of weeks back, reprises an important issue for everyone studying nationalism in China: to what extent should we really understand the phenomena that get labelled “Chinese nationalism” in those terms?

Consensus at the top? China’s opportunism on Diaoyu and Scarborough Shoal

Posted: November 28, 2012 Filed under: Academic debates, China-ASEAN, China-Malaysia, CMS (China Maritime Surveillance), Diaoyu, FLEC & Ministry of Agriculture | Tags: 1988 Spratly Battle, anti-Japanese protest, ASEAN and South China Sea, China-ASEAN, Chinese foreign policy, Chinese public opinion, COC, Code of Conduct, Diaoyu Islands, escalation, 钓鱼岛, Johnson South Reef Skirmish, nationalism card, PRC foreign policy, PRC maritime law enforcement, PRC-Japan, reactive assertiveness, Scarborough Shoal 黄岩岛, south china sea, uses of public opinion 2 CommentsIn last week’s Sinica Podcast, M. Taylor Fravel discussed the March 1988 Sino-Vietnamese battle in the Spratly Islands, recounting how the PLAN Commander was moved from his post afterwards as a result of his unauthorized decision to open fire on the Vietnamese Navy.

This could make the 1988 battle appear as a historical example of uncoordination in the PRC’s behaviour towards the outside world — a rogue commander taking foreign policy into his own hands. However, the decision to send the Navy in to establish a presence on unoccupied reefs in the Spratlys was a centralized, high-level one.

Today, the Chinese Navy is better equipped and better trained, so the chances of something similar happening are small. The unwavering non-involvement of the PLAN in China’s maritime territorial disputes, even as tensions have risen to boiling point, is a testament to the navy’s professionalization, and a site of consensus among China’s policymakers. The US Department of Defense in 2011 presciently pinpointed (see p.60) the increasing use of non-military law enforcement agencies to press China’s claims in disputed waters as an important component of PRC policy. Since then, this approach has become ever-more salient.

China’s maritime law enforcement fleets have long been seen as a source of policy disorganization, both within China and abroad; back in 2002, for example, the Hainan Provincial NPC delegation tabled a motion to establish a unified maritime law-enforcement fleet.

But in the podcast Fravel drew attention to how this year the China Maritime Surveillance and Fisheries Law Enforcement fleets have actually coordinated rather well, both with each other and with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in advancing China’s maritime claims.

The problem with big claims about Chinese nationalism

Posted: November 4, 2012 Filed under: Academic debates, China-Japan, Diaoyu | Tags: anti-Japanese protest, Chinese foreign policy, Chinese nationalism, Chinese public opinion, demonstrations, Diaoyu Islands, Jessica Chen Weiss, nationalism, protests, public opinion, Robert Ross, Robert S. Ross, Senkaku, Sino-Japanese relations 1 CommentRobert S. Ross built a reputation over the 1980s and 1990s as one of the leading realist analysts of Chinese foreign policy. He published a seminal article in 1986 highlighting the importance of the US-USSR-PRC “security triangle” in explaining China’s behaviour under Deng Xiaoping, and after the Cold War made a successful switch into the richer and murkier terrain of the domestic security situation of the CCP leadership and its relationship to Chinese foreign policy.

Ross’s shift in emphasis towards the importance of domestic factors in explaining China’s behaviour towards the outside world was foreshadowed in his 1986 piece, which noted:

The relative importance of domestic politics has been a function of the range of choice allowed by the pattern of triangular politics [ie. the international environment]. When the range of choice was narrow, domestic politics had a small impact on China’s US policy. When the choices expanded, domestic critics wielded greater influence on foreign policy making.

In recent years, the Boston College professor and Harvard Fairbank Center associate has become very keen on the idea of nationalistic public opinion as a singular driving force behind the Communist Party’s foreign policy.

One early example was 2009’s ‘China’s Naval Nationalism’, which argued the PLA Navy’s modernization, especially its aircraft carrier program, was irrational and against China’s national interest. Instead, Ross wrote, “widespread nationalism, growing social instability, and the leadership’s concern for its political legitimacy drive China’s naval ambition”. This contention provoked a lengthy response from Michael Glosny and Phillip Saunders, who pointed out a range of national interest arguments that could be made for China’s naval modernization.

Evidently unmoved by this critique, a 2011 piece in the National Interest produced a greatly expanded list of PRC foreign policy actions designed to appease nationalist public opinion. Although there is no question that domestic public opinion, including its loudly hawkish trends, form an element of the CCP leadership’s decision-making environment, there are plaisible interest-based explanations for each of the examples on Ross’s list:

- The Impeccable incident in the South China Sea, in which a motley flotilla of fishing boats and patrol ships harassed a US surveillance ship. (Undesirability, from the PRC’s strategic perspective, of having US surveillance ships gathering data on its new submarine facilities at the bottom end of Hainan Island?)

- China’s intransigence at the Copenhagen climate change conference. (PRC delegation was led by the National Development and Reform Commission, which has responsibility for China’s economic planning and thus a vested interest against binding carbon reduction targets. Repeated studies showing Chinese people to be very climate-aware.)

- The harsh reaction to the announcement of US arms sales to Taiwan in 2010. (US military support for Taiwan stands between the PRC and fulfillment of its long-stated “sacrosanct mission” of “national reunification”. This could be termed a tenet of nationalist ideology, but it is a very long-standing one, rather than a recent development.)

- China’s repeated strong protests against joint US-Korean naval exercises in the Yellow Sea in June-July 2010. (Also cited as an example of media-driven nationalist influence by Michael Swaine & M. Taylor Fravel, though China wound back its statements somewhat when further exercises were announced in November 2010.)

- The PRC’s lack of denouncement of North Korea for the sinking of the Cheonan. (Perhaps because North Korea is China’s only true ally in East Asia?)

- The party-state’s overreaction to the September 2010 detention of Captain Zhan, the Chinese fisherman who rammed a Japanese Coastguard vessel near the Diaoyu Islands. (Japan’s deviation from the established precedent of quickly releasing detained Chinese fishermen? Opportunity for China to use its burgeoning maritime law enforcement fleets to advance its sovereignty claims?)

- Denouncing the awarding of the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize to Liu Xiaobo. (CCP opposition to democracy activism in China?)

- The treatment of Google. (The refusal to censor its search results?)

“[T]he source of all the aggressive Chinese diplomacy,” wrote Ross, is “the party’s effort to appease China’s nationalists”.

The same list has been extended and wheeled out again in the latest edition of one of the US’s top foreign policy journals Foreign Affairs, in a piece called ‘The Problem With the Pivot’.

For the benefit of any time-stretched readers, my problems with Ross’s argument, detailed below, are that it:

- Relies on the mistaken premise that there has been a severe economic downturn in China since 2009, from which a legitimacy crisis has ensued.

- Wrongly assumes that China’s assertive foreign policy actions are seen as such by nationalist sections of Chinese public opinion.

- Discounts the huge strategic and economic interests China has, or perceives it has, in advancing its claims to disputed islands and maritime space.

- Claims, in the face of strong evidence to the contrary, that the Chinese party-state is unable to prevent anti-foreign protests.

- Argues that the recent protests over Diaoyu caused the PRC’s foreign policy escalation, dismissing how protests might help in advancing the government’s policy objectives.

Songs of the disputed seas: patriotic music from the anti-Japanese protests and Paracels War

Posted: October 1, 2012 Filed under: Diaoyu, TV | Tags: anti-Japan, anti-Japanese protest, Battle Hymn of the Paracels, Beijing, China, Chinese nationalism, Chinese patriotism, Chinese TV, 米粒, demonstration, Diaoyu Islands, 钓鱼岛, 陆海涛, 西沙战歌, Japan, Lu Haitao, Maoism, march, Mi Li, nationalism, nationalist art, Paracels, patriotic songs, patriotism, Senkaku, Sino-Japanese relations, Star Avenue, territorial dispute, translation, 星光大道, 中国领土 2 CommentsCDs with a song (one song) were being handed out for free at the anti-Japanese protests on September 18.

The song was specially recorded after the protests began by Lu Haitao 陆海涛 and Mi Li 米粒, two moderately successful contestants from the CCTV talent show Star Avenue. (Lu made the grand final, Mi won one round of the competition last year.)

I don’t know who bankrolled its production, and neither did any of the other bemused attendees who, like me, rushed over to grab whatever everyone else was grabbing. But according to this BBS post, Mi Li herself shelled out her own money for 1000 of the CDs to be pressed.

As horrid as its mixture of Han-chauvinist and Maoist nationalism is, i have found it compulsive listening….and strongly advise against giving up before you get to 2 minutes in — for a spectacularly hammy rap section awaits there. Yes, Diaoyu RAP!

I particularly love the way the guy’s “之” syllables just become growls. Being based on the language of officials during imperial times, it’s not surprising that the Mandarin language is amenable to the kind of haughty authority the song attempts to voice.

As for the diva, well, she may be rather nastily screechy, but not nearly as screechy as the lady who sang ‘Battle Hymn of the Paracel Islands’ to celebrate China’s victory over hapless South Vietnamese remnants there in 1974:

Source for the background image is Chineseposters.net.

A cautionary tale from the Beijing Youth Daily: misfortune of one driver in the Xi’an anti-Japanese protests

Posted: September 23, 2012 Filed under: China-Japan, PRC News Portals, State media | Tags: anti-Japanese protest, Beijing Youth Daily, China protest, Chinese media, Chinese nationalism, Diaoyu, Diaoyu Islands, 钓鱼岛, mob violence, popular protest, PRC-Japan, public opinion, Sino-Japanese relations, Xi'an, 北京青年报, 反日游行, 打砸 5 Comments

Scene of the attack on father of two Li Jianli during anti-Japanese protests in Xi’an, September 15, 2012. Mr Li’s wife, Mrs Wang, featured in the story translated below, is seen cradling her husband’s head.

First came the exhortations to “rational patriotism“, accompanied by satisfying news of China’s government’s “strong countermeasures” — how many law–enforcement ships, how many Chinese fishermen heading to Diaoyu, how surprised Noda was at the strength of China’s response, and even a belated appearance by the PLA Navy in the area.

On Monday afternoon the armada of Chinese fishing boats was a lead photo on the PRC’s top five news portals, while arrests for protest misbehaviour were dominant headlines. E.g.:

There were many more such cautionary tales in the wake of last weekend’s violent riots across China (photos, photos & more photos): police getting on Weibo to seek the perpetrators of patriotic smashings, and subsequent well-publicised arrests in Guangzhou and Qingdao and likely elsewhere. (English-language story from today, September 22, is here.)

Yesterday the Beijing Youth Daily published a detailed, vivid and gory account of how Li Jianli, a Xi’an family man, was left with brain damage just for driving a Toyota Corolla in Xi’an. As the article describes, Li’s wife got out and tried to convince the protesters not to smash the car with a few “good sentences”, including a pledge to never again buy a Japanese car, but this was all to no avail as someone smashed his skull with a D-lock.

Perhaps to avoid demonizing the protesters, or maybe to provide a positive exemplar (after all, what politicised human interest story would be complete without one of those?), the piece concentrates on the intersection of Li Jianli’s tragic tale with that of a protest-planner-turned-saviour, 31-year-old tool peddler Han Pangguang. When Han heard about Japan’s plan to nationalise the Diaoyus he collected several hundred signatures from other sellers in the marketplace and applied to hold a protest. But as soon as he heard that the protests had turned violent, according to the article, he suddenly turned his attention to saving those threatened by the violence.

The injection of Han Chongguang into the story, of course, serves to support the official line that it was not protesters, or anti-Japanese sentiment, that was the problem, but rather, illegal elements who hijacked the protests.

Nonetheless, the piece provides a fascinating first-hand accounts of the chaos of September 15 in Xi’an.

~

On September 15, a Xi’an driver’s misfortune

Beijing Youth Daily, September 20, 2012

By Li Ran

Fifty-one-year-old Xi’an resident Li Jianli was the breadwinner for his family, but now he lies rigid in a hospital neurosurgery ward.

Li Jianli’s left arm and leg have begun to regain partial movement, but the whole of the right side of his body remains limp. He can slowly bend his right leg, but his right arm and hand just flatly refuse to obey orders. His speech faculties have been badly damaged; he can only say simple 1-2 syllable phrases like “thanks” and “hungry”.

Xi’an Central Hospital has made a diagnosis: open craniocerebral injury (heavy).

Luckily, over the past three days in intensive care he has basically returned to consciousness. As soon as he thinks of what happened to him on September 15, his eyes turn red and silent tears begin to flow. His left hand struggles up to wipe them away.

At 3.30pm that day he was smashed on the head with a U-shaped lock, which penetrated the left side of the top of his head, shattering his skull. He fell down, unconscious, and thick blood and cranial matter spilled out onto the ground. Soon, bloody foam was coming out of his mouth.

The halting of the anti-Japan protests (and bagpipes in Beijing)

Posted: September 19, 2012 Filed under: China-Japan, Diaoyu, Global Times, PRC News Portals, State media | Tags: anti-Japanese protest, Beijing, Beijing News, Beijing PSB, CCTV, Chinese internet, Chinese media, Chinese nationalism, Diaoyu, Global Times, Huanqiu Shibao, Japanese embassy, news portals, Public Security Bureau, Yanshaqiao 3 CommentsLast night i tweeted, ill-advisedly, that since the official media remain in saturation-coverage mode over Diaoyu, i thought the protests would continue today. I quickly found i was emphatically wrong.

I knew my hunch was mistaken even before i arrived at the embassy area this morning. A glance over some of the newspapers suggested a qualitative shift in the coverage, which i had missed last night: while the quantity of Diaoyu news remains overwhelming, the emphasis is now on good news much more than the ghastly deeds of the Japanese.

The Beijing News (pictured above), for example, led with “12 [Chinese] official boats patrolling at Diaoyu“, and put the “Two Japanese right-wingers, falsely claiming to be fishing, land on Diaoyu” on page 8. Likewise, the Huanqiu Shibao had “12 Chinese boats approach Diaoyu” (image not available online at present) , and i have failed to find the Japanese landing story anywhere in the paper.

This pattern echoed precisely what happened in the online news sector yesterday. The Japanese right-wing landing was a dominant headline (ie. large-font at the top) on all of the top five PRC news portals as at 4.30 yesterday afternoon — understandable given the story’s sensationally provocative nature as summed up in the text of the headlines, which all slapped the move with the “serious provocation” tag. But by 8.30pm the story had been relegated to the sub-dominant headlines (ie. small-font, still at the top) in favour of the presence of China’s government ships patrolling in Diaoyu waters, which at that point numbered eleven (it’s now up to 14).

When my buddy and i arrived at Yanshaqiao, the embassy area, we were greeted with the following text message from the PSB:

Beijing Municipal Public Security Bureau alerts you: In recent days the broad masses have expressed their patriotic enthusiasm and wishes spontaneously, rationally and in an orderly way. Protest activities have now concluded, and the embassy area has returned to normal traffic conditions. It is hoped that everyone will express patriotic enthusiasm in other ways, will not come again to the embassy area to protest, and will cooperate with relevant authorities to jointly uphold good traffic and social order. Thankyou everyone for your understanding and support — Beijing City Public Security Bureau.

It doesn’t get any clearer than this. The protests were acceptable, indeed laudable, to the authorities until today. Now they are banned.

Sure enough, when we reached the street corner i had to check the road sign to know whether i was in the same place as i had been the past few days. It was full of fast(ish)-moving traffic, and there was not a single five-starred red flag in sight.

We walked up towards the embassy, and quickly encountered a marching column of about 100 police. Beyond, individual police officers were stationed approximately 3 metres apart for the next 800 metres or so.The People’s Armed Police and barricades in front of the Japanese embassy remained, and in the carpark of the International Youth University opposite the embassy we found busloads of PSB officers waiting in reserve.

All up, there appeared to be approximately as many police as there had been over the previous days of thousands-strong protests. That is to say, there were probably less plain-clothes officers and roughly the same number of uniformed ones, whose function had changed from facilitation and crowd control to prevention of any sign of protest whatsoever. In 45 minutes of wandering up and down, in and out, literally the only Chinese flags i saw were those covering up the signs on the Japanese restaurants.

One of many Japanese (and even Korean) restaurants on Beijing’s Chaoyang Park Rd, diagonally opposite the Japanese embassy, September 19, 2012

To (hopefully, temporarily at least) end this dark chapter on a happier note, check out this 特牛 bagpipe-player, kilt and all, filmed during the massive demonstrations yesterday. William Wallace’s military spirit, or a fiercely patriotic Chinese Scot — who knows? Also the police presence.

Apologies for the appalling jerkiness of the video (i blame the police and their determination to keep everyone moving), but for me it would be worth copping that just to catch a glimpse of him:

A lazy Sunday afternoon at the Beijing anti-Japan protests

Posted: September 17, 2012 Filed under: China-Japan, Diaoyu | Tags: activism, anti-Japanese protest, Baodiao, China protest, demonstrations, Diaoyu, Diaoyu Islands, mobilisation, nationalist demonstrations, Senkaku Islands, Sino-Japanese relations 5 CommentsThe first thing that struck me about the anti-Japanese protests in Beijing on Sunday was how helpful the authorities were, to me and everyone else who went.

Being the goose that i am, i went to the wrong embassy — the old one on Ritan St that’s awaiting demolition. I wasn’t alone, however, for a handful of locals had also made the same mistake. The policemen on duty very obligingly told us where to go, and the options for getting there, and even let us listen in on their radio for the latest update, which was that about 350 people were over there protesting.

I combined for a taxi with a couple from Hebei whose purpose turned out to be similar to mine: they were just going down there to have a look.

When the taxi could take us no further, the police were only too happy to help once again. Verbatim conversation:

Hebei fellow: Where should we go?

Policeman: Are you here to work, or to protest?

Hebei lady: Umm…protest.

Policeman (pointing across the road): That way and turn right.

The protest zone bore all the hallmarks of a well-organized event venue, starting with the roadblocks and the hundreds of evenly-spaced “volunteers” lining the path leading towards the embassy. I asked several of the latter how they came to be here and where they got their red armbands, but the closest i got to answer was, “Uhhh…” (looking around at her friends), “this is not good to say.”

Later on, i asked another young woman, who told me she was from a neighbourhood committee. A friend who i met up with suggested that they were probably also drawn from the ranks of grassroots-level government workers.

Outside the embassy it became apparent that the whole purpose of the roadblocks to was create a long racetrack with hairpin bends at both ends, around which the groups of protesters could march in safety and captivity, under the watchful eyes of the armed police.

Around and around they went, in four or five groups whose numbers anywhere from 50 up to about 200. They carried their banners, chanted their slogans, and occasionally threw volleys of plastic water bottles over the motionless rows of People’s Armed Police as they passed by the embassy. The result:

At one point i said something about the “PLA brothers” across the street, which a fellow onlooker quickly corrected: “The PLA is for attacking the Japanese, the PAP is for attacking the Chinese.” Indeed, the armed police would have been feeling a bit nervous after what happened yesterday (more photos from Netease):

But in the three hours or so that i stood there, i didn’t hear anything remotely controversial yelled — for example, the chant of “打倒汉奸”, or “down with Chinese traitors” that is heard around 1:41 in this video from Saturday’s protests.

The most remarkable thing about the slogans was the frequency with which the protesters came past yelling at the crowds of onlookers (leaders//followers): “Chinese people!//Join in!” Sometimes this bolstered their numbers by one or two, but on most occasions those around me (directly opposite the embassy) stood staring as passively as the laowai in their midst.

It was getting late in the day by the time i got there, so some of the spectators had probably marched around the track a few times, but genuinely angry people really did seem to be a fairly small minority. In contrast, despite the marchers’ direct appeals, the great majority of those present were just there to observe the spectacle of a protest in the heart of the Chinese capital.

Nonetheless, lest i fall into the trap of Beijingcentrism after but a single weekend here, the following is a selection of photos of the havoc wreaked around the country by the mass protests of, according to Xinhua, up to 10,000 in more than 50 other cities.

Eric Fish is right to point out the opportunity that the Diaoyu affair has presented to the ruling party in terms of diverting the Chinese people’s attention away from its Eighteenth Congress, but whether it proves to be a “godsend” is not certain. As Adam Minter and Evan Osnos have both recently observed, since the Chinese party-state has no way of satisfying the demands it has unleashed, this could spell trouble.

Police car in Chengdu (from Shanghaiist)

The Communist Party has successfully neutralized these types of nationalist mobilization in the past through a combination of suppression of activism and positive media coverage of Japan. The question is how they will manage this in the internet era.

“The whole world’s Chinese people are going”: decisive moments, and the perils of Diaoyu nationalism

Posted: August 19, 2012 Filed under: China-Japan, CMS (China Maritime Surveillance), Comment threads, Diaoyu, FLEC & Ministry of Agriculture, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, PRC News Portals, State media, Weibo | Tags: anti-Japanese protest, Chinese nationalism, demonstrations, Diaoyu, Diaoyu activists, 钓鱼, 警车被砸, Hong Kong, imagery, Japan Coast Guard, nationalism, pincer attack, Qifeng-2, Senkaku, 日本船夹击 4 CommentsLocated to the northeast of Taiwan, just under halfway to Okinawa, the Diaoyus have been controlled by Japan since the first Sino-Japanese War in 1895. China (both of them) claims that the islands were imperial Chinese territory before that, so Japan’s annexation of them in 1895 was an illegal land grab, and that they should have been returned to China at the end of WWII under the Potsdam Declaration.

The Diaoyus are not tiny coral atolls like the Spratlys and Paracels. They are (well, five of the eight features) genuine islands, albeit barren and uninhabited. Like the South China Sea islands, however, there’s believed to be black-gold in their bellies.

While the competition for the oil and gas resources can basically explain the two sides’ determination to claim sovereignty, on the Diaoyu the influence of nationalistic public opinion on the Chinese government’s behaviour appears more significant than on the South China Sea. To begin with, the public ill-will on both sides is deep-seated and getting worse, and political opportunists have the opportunity and motive encourage and exploit this.

The ICG’s Stephanie Kleine-Ahlbrandt recently commented that the leaders of China and Japan have little “political capital” to spend on defying “nationalist or populist sentiment”. In this excellent interview, SKA identifies nationalist sentiment as a constraint on governments’ ability to compromise or back down during a dispute. There are counter-examples where Chinese and Japanese leaders have appeared to defy pressure to be uncooperative and confrontational, such as Noda’s government’s speedy release of the recent protagonists, and China’s decision not to send patrol boats to guard them. But the two countries’ recent record suggests this has been difficult at times in the past.

Public opinion offers an explanation for what learned observers consider to be China’s counterproductively hardline stance in the previous Diaoyu confrontation in September 2010 (itself a response to Japan’s abnormally trenchant action in detaining an infringing Chinese fishing boat captain for several weeks rather than releasing him swiftly, as they did yesterday). And the ill-will on the part of both publics may have had a lot to do with the non-implementation of a deal negotiated back in 2008 for cooperative development of some of the oil and gas deposits in the area.

Nationalist activists on both sides are true believers in their cause, so even where their actions may be deliberately incited and/or tacitly sanctioned by their governments, they nonetheless impact the dispute by necessitating responses from the other side. Once the Qifeng-2 escaped the clutches of the Hong Kong police and sailed beyond the reach of the PRC authorities, for example, Beijing had little or no control over whether the passengers of the Qifeng-2 would actually manage to set foot on the island last Wednesday.

At the same time, the PRC government has on numerous occasions proved willing and capable of preventing Diaoyu activists from making their journey in the first place, whether in Hong Kong or on the way to the Diaoyus. This suggests that where Chinese citizens’ action has an impact, a decision to allow this must be made at some level of leadership — which could be made as low as a local PRC Coastguard official, a China Maritime Surveillance branch commander or as high as the Politburo Standing Committee.

Such decisions have certain easily foreseeable outcomes (a diplomatic incident of some kind was almost inevitable once the Qifeng-2 left PRC-controlled waters) yet their exact consequences in international politics are unpredictable. Moreover, these leadership choices occur in a domestic political context, which in China includes not only party politics and ideology, but also domestic nationalist discourse — what groups of people are thinking about where the country is or should be going.

The recent episode illustrates vividly what a dynamic and contested process of simultaneous group interpretation and elite engineering ‘nationalism’ really is.

Chinese activists jump from the Qifeng-2 onto Diaoyu Island, carrying PRC and ROC flags, August 15, 2012.

Take the above photo, for example — taken at the critical moment when the activists jumped ashore. Is the ROC flag something to be proud of, or ashamed? Is its appearance here a symbol of Chinese unity or division?

Weibo’s microbloggers appeared to see it more as a sign of cross-straits collaboration, enthusiastically forwarding it around as proof that the activists had made it onto the island. According to Weiboscope, it was at time of writing the most-forward image of the incident.

The PRC internet authorities also don’t seem to object to its dissemination, intact, on Weibo and other online news sources (see here and here). In stark contrast, however, the propaganda authorities overseeing China’s print media clearly saw it very differently to the online public, for among China’s main newspapers the ROC flag was either cropped out, crudely paint-bucketed red, or otherwise blotted out in very nearly every instance (among hundreds of covers on Abbao i found only one exception, the obscure Yimeng Evening News). The same was the case on mainland TV.

This might have had something to do with the gloating the official media have recently been engaging in over the fact that a group of Diaoyu activists from Taiwan last month waved a PRC flag to proclaim sovereignty from seas near the islands — even though they got an escort from the ROC Coastguard.

There was also perhaps the inconvenient fact that this time around the ROC authorities had pressured local activists into abandoning their trip and refused all but the most elementary assistance to the Qifeng-2 when it tried to stop past on its way from Hong Kong to the Diaoyus. According to the Global Times (English):

Earlier on Tuesday, the ship anchored in the waters near Taichung, after the local marine authority denied their application to reach land. The activists were only able to procure limited freshwater supplies.

The news on Tuesday that activists from Fujian who had wanted to join the expedition had canceled their plans due to “reasons of weather and procedure” also raised the question of exactly which of the ‘three regions’ (Taiwan, Hong Kong and the PRC) actually represents the Chinese people best. The top comments on Phoenix’s 111,000+ participant thread for ‘Mainland activists cancel trip to Diaoyu, citing weather and procedures‘:

“I know the reason you can’t go, I understand, backup is lacking, speechless.” [11,790 recommends]

“Clearly a crock of shit. Whoever believes it has got water in their brain.” [8166]

“Such a loss of face………speechless. Support the Hong Kong and Taiwan compatriots.” [5157]

“The whole world’s Chinese people are going, it’s just the mainland…” [4291]

Once again, the idea of the PRC government’s rule being based on anything that can be usefully understood as “nationalist legitimacy” appears questionable. And the idea that the party-state is trying to build up such “nationalistic legitimacy” via its foreign policy actions looks patently absurd.

On the topic of absurdity and Hong Kongers’ Chinese patriotic credentials, Kong Qingdong didn’t escape the participants of the Tencent thread above:

“This is the Hong Kong people that Kong Qingdong said are running dogs! Is he cross-eyed?” [17,489]

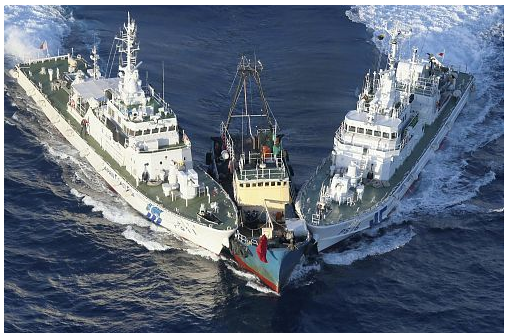

The other widely-circulated decisive-moment photograph from the scene of the confrontation further illustrates how deficient in nationalistic credentials the PRC state is:

This stunning image cast the Chinese activists in an intensely helpless position. When i first saw it i couldn’t believe that it was real; Photoshop-wielding nationalist students wanting to raise a rabble could hardly have done better. Taken by a Japanese photographer for the Yoimuri Shimbun, it makes the two Japanese Coastguard boats look positively evil.

That’s probably why it has been placed on newspaper covers all over China (once again, Abbao can illustrate), and pumped around the internet by the People’s Daily website’s Weibo account.

But it also rams the viewer with an almost unavoidable question: why was no-one there to help?

The giant comment threads on the portals indicate that exactly this kind of question is in the forefront of many ordinary PRC people as they read the news on the internet.

Perhaps this contributed the speed and fervour with which Sunday’s protesters turned their destructive powers onto the authorities:

“Do not let patriotism become a G-string for violence”: China Youth Daily

Posted: August 20, 2012 | Author: Andrew Chubb | Filed under: Article summaries, China-Japan, Comment threads, Diaoyu, Mouthpieces, PRC News Portals, State media | Tags: anti-Japanese protest, China Youth Daily, Chinese internet news portals, Chinese media, Chinese nationalism, Chinese patriotism, Communist Youth League, Diaoyu, internet censorship, Netease, news portals, phoenix, Sina | Leave a commentChina Youth Daily 中国青年报 front page, August 20, 2012

China Youth Daily, August 20, 2012, p.1

Cherish patriotic fervour, sternly punish violent smashing 呵护爱国热情 严惩打砸暴行

Cao Lin 曹林

—– SORRY FOR THE UNREADABLE UNDERLINING YESTERDAY, MOUSEOVER TRANSLATIONS ARE NOW IN EFFECT, THANKS ONCE AGAIN DANWEI.COM —-

[. . .] On the morning of the 19th of August, there were gatherings of different sizes in more than 10 cities including Beijing, Jinan, Qingdao, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Hangzhou.

Xinhua journalists reported that in these cities the police were present at all the mass gatherings to maintain order, and the protest marches were on the whole peaceful. However, from numerous eyewitness descriptions, there were some places where extremely incautious and irrational behaviour occurred. Some people received some ulterior-motivated incitement, and smashed their compatriots’ Japanese cars. It was very unsightly.

{“Boycott Japanese goods” slogans are fine, displaying a clear mind, but smashing compatriots’ cars and ruining private property is “clearly stupid, seriously harming social order, the city’s image, and China’s image.”}

Several days ago a netizen somewhere in Sichuan sent a letter to local officials expressing their “concern about upcoming anti-Japanese rallies” in light of their deleterious effects last time. The local officials replied, thanking them for the message, and saying that their concern was not without reason. In expressing anti-Japanese patriotism, [the officials said], some people had rushed onto the streets, blocking the way for Chinese people, smashing Chinese people’s cars and shops and harming their own compatriots. The result was helpful to Japan, and this kind of stupid thing cannot happen again.

[. . .] These stupid acts are not aiguo but haiguo. They will never attract praise and can only make real patriots feel ashamed.

Read the rest of this entry »