Comparison of Vietnam and China’s joint statements, 2011-2017

Posted: February 3, 2017 Filed under: China-Vietnam, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, South China Sea | Tags: arbitration, China-Vietnam, China-Vietnam joint statement, China-Vietnam relations, joint communique, Nguyen Phu Trong, nine dashed line, nine-dash line, Philippines vs China arbitration, Sino-Vietnamese relations, south china sea, South China Sea arbitration, UNCLOS, UNCLOS and South China Sea, Vietnam-China joint statement 2 Comments

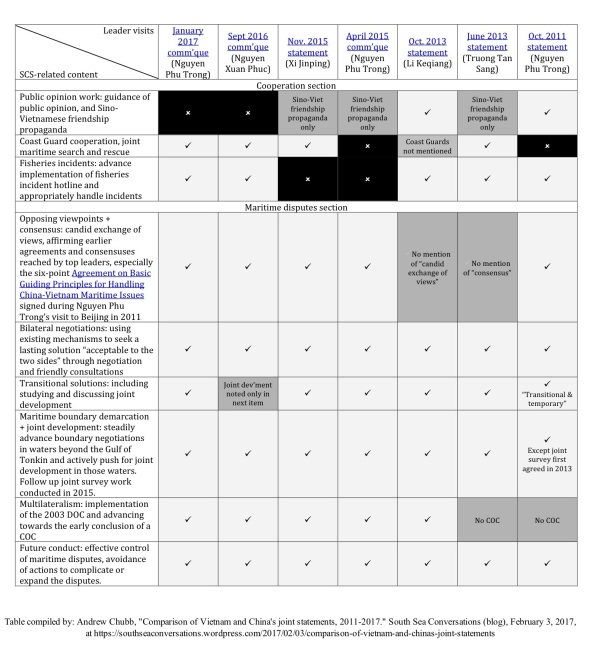

Comparison of Sino-Vietnamese joint statements since 2011 (click to enlarge). Links to sources: January 2017 communique (Nguyen Phu Trong visit to China); Sept 2016 communique (Nguyen Xuan Phuc visit to China); Nov. 2015 statement (Xi Jinping visit to Vietnam); April 2015 communique (Nguyen Phu Trong visit to China); Oct. 2013 statement (Li Keqiang visit to Vietnam); June 2013 statement (Truong Tan Sang visit to China); Oct. 2011 statement (Nguyen Phu Trong visit to China).

East Asia Forum has kindly published a piece from me on recent developments in Sino-Vietnamese relations. To supplement it, i’m posting here a table comparing the South China Sea-related elements of the last 7 joint statements between the two.

The comparative table was the basis for the article’s argument that General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong’s visit to Beijing last month did not involve any softening of Vietnam’s position on the issue.

According to a knowledgeable Vietnamese source, there are three types of Sino-Vietnamese bilateral joint statements issued after high-level meetings. In ascending order of importance these are:

- Joint press release (联合新闻公报, thông cáo báo chí)

- Joint communique (联合公报, thông cáo chung)

- Joint statement (联合声明, tuyên bố chung)

These documents are often not released in English, and some of the translations that have appeared have been incomplete or unreliable, so the table above compares the Chinese full text as published by state media (links are in the caption area above).

The table also includes an item, not discussed in the EAF article for space reasons, on cooperation in public opinion work. In the 2011 joint statement, the two sides pledged cooperation on “strengthening public opinion guidance and management” – which, in the context of several weeks of anti-China protests through the middle of that year, was tantamount to a Vietnamese undertaking to dampen anti-China sentiments.

Interestingly, however, there has been no analogous item in the recent joint documents — even after another, even more intense, wave of anti-China sentiments burst forth in 2014 during the HYSY-981 oil rig standoff. Its omission from subsequent documents might indicate an acceptance on China’s behalf of the strength Vietnamese nationalist sentiments that flow in its direction at times of heightened tensions. Perhaps also an acknowledgement that Hanoi is already doing what it can to promote Sino-Vietnamese friendship? Any other readings?

The EAF piece is reposted below. Based on some early feedback, i should have been clearer that in suggesting . . .

China may have pulled back from its pursuit of particular claims that have no basis in international law

. . . i do not mean the PRC has seen the light and is abandoning all claims deemed unlawful in the UNCLOS arbitration. Just that there are some unlawful aspects of China’s claims that it is no longer pushing, and this has removed some of the major drivers of Sino-Vietnamese tensions.

As always, further comments, arguments, additions and corrections are much appreciated.

China’s latest oil rig move: not a crisis, and maybe an opportunity?

Posted: June 27, 2015 Filed under: China-Vietnam, South China Sea, Western media | Tags: China-Vietnam, China-Vietnam relations, Chinese foreign policy, HYSY-981, Nam Con Son, Nam Con Son Basin, nine dashed line, oil and gas, south china sea, straight baselines 1 Comment

Location of Chinese drilling rig HYSY-981, with approximate equidistant lines between Hainan, the Vietnamese coast, and the disputed Paracel Islands (map by Greg Poling)

On June 25, China’s Maritime Safety Administration announced the gargantuan drilling rig HYSY-981 had returned to the South China Sea for more drilling operations, raising concerns of a return of the serious on-water clashes last year.

Here we go again was a widespread sentiment on Twitter. The apparent expectations of impending repeat showdown appear to result in part from the headline of a widely-shared Reuters story, ‘China moves controversial oil rig back towards Vietnam coast‘. This might be technically correct (i’m not sure exactly where the rig was before) but this year’s situation is quite different to last year’s.

Serious on-water confrontation is unlikely this time around because the rig is positioned in a much less controversial area. It is a similar distance from the Vietnamese coast (~110nm) but much further from the disputed Paracel Islands (~85nm), and much closer to the undisputed Chinese territory of Hainan (~70nm, compared to more than 185nm in 2014).

As explained below, the parallels between this area and others where China has objected — sometimes by coercive means — to Vietnamese oil and gas activities, make the latest move a good opportunity to grasp an important aspect of the PRC’s position in these disputes, and pin down some of its inconsistencies.

China’s Information Management in the Sino-Vietnamese Confrontation: Caution and Sophistication in the Internet Era

Posted: June 9, 2014 Filed under: China-Vietnam, Global Times, PRC News Portals, South China Sea, State media, TV, Weibo, Xinhua | Tags: CCP Propaganda Department, China-Vietnam, China-Vietnam relations, Chinese foreign policy, Chinese internet, Chinese internet censorship, Chinese patriotism, 理性爱国, 舆论引导, 西沙, HYSY-981, internet censorship, paracel islands, Paracels, Propaganda department, rational patriotism, Sino-Vietnamese incidents, south china sea, 南海, 南海问题, 宣传部, 海洋石油-981, 中越, 中越撞船 2 CommentsJamestown China Brief piece published last week:

~

China’s Information Management in the Sino-Vietnamese Confrontation: Caution and Sophistication in the Internet Era

China Brief, Volume 14 Issue 11 (June 4, 2014)

After the worst anti-China violence for 15 years took place in Vietnam this month, it took China’s propaganda authorities nearly two days to work out how the story should be handled publicly. However, this was not a simple information blackout. The 48-hour gap between the start of the riots and their eventual presentation to the country’s mass audiences exemplified some of the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) sophisticated techniques for managing information during fast-breaking foreign affairs incidents in the Internet era. Far from seizing on incidents at sea to demonstrate China’s strength to a domestic audience, the official line played down China’s assertive actions in the South China Sea and emphasized Vietnamese efforts to stop the riots, effectively de-coupling the violence from the issue that sparked them. This indicated that, rather than trying to appease popular nationalism, China’s leaders were in fact reluctant to appear aggressive in front of their own people.[1]

By framing the issue in this way, China’s media authorities cultivated a measured “rational patriotism” in support of the country’s territorial claims. In contrast to the 2012 Sino-Japanese confrontation over the Diaoyu Islands, when Beijing appears to have encouraged nationalist outrage to increase its leverage in the dispute,[2] during the recent incident the Party-state was determined to limit popular participation in the issue, thus maximizing its ability to control the escalation of the situation, a cornerstone of the high-level policy of “unifying” the defense of its maritime claims with the maintenance of regional stability (Shijie Zhishi [World Affairs], 2011).

Creative tensions and soft landings: Wang Yizhou explains China’s foreign policy agenda

Posted: December 17, 2013 Filed under: Academic debates, China's foreign relations, China-ASEAN, China-Japan, China-US | Tags: Carnegie-Tsinghua Center, China-Japan, China-North Korea relations, China-US relations, China-Vietnam, China-Vietnam relations, Chinese foreign policy, Chinese foreign policy scholars, Chinese strategy, creative tensions, 王逸舟, New kind of great power relations, north korea, Paul Haenle, peripheral diplomacy, PRC foreign policy, Sino-American relations, Sino-Japanese relations, Sino-Vietnamese relations, south china sea, Wang Yizhou, Xi Jinping foreign policy 4 CommentsPeking University Professor Wang Yizhou, one of China’s top foreign policy scholars, did an interview for the excellent new Carnegie-Tsinghua podcast last month (Part 1 and Part 2), covering a very broad sweep of China’s emerging foreign policy, regional strategy, territorial disputes, global role, and bilateral relations with the US.

His main points are noted below, starting with regional strategy and China’s maritime territorial disputes. I’ve just done this as an exercise to try to better grasp the significance of what Wang says; for most people it’s probably better to just go listen to the podcast. The italicized blockquote bits are a mix of direct quotes and paraphrasing.

~

Xi’s task: a “soft landing” for the South China Sea dispute

Professor Chen Jie explains the Spratly triangle

Posted: August 27, 2012 Filed under: Article summaries, China-Philippines, China-Vietnam | Tags: 1988 Spratly Battle, Chen Jie, China-Philippines relations, China-Vietnam relations, 陈杰, Jie Chen, SBS Radio, Sino-Vietnamese relations, spratly islands, Vietnam-Russia 3 Comments–Note: apologies to email subscribers for the incomplete draft sent out just now. I didn’t realise the Iphone app could interpret an errant finger swipe as an instruction to “publish now”. I will hopefully finish it off today after i’ve spoken to some more friends.–

In the dispute over the Spratly Islands, a China-Vietnam-Philippines triangle of active claimants has taken shape, with external great powers the US, India, Russia and perhaps even Japan lurking, anxious about possible trouble and eager to seize any strategic opportunity. The interview translated here, recorded in November 2011 following several months of intense diplomatic maneuverings, offers an excellent recap of how we arrived at the more direct competition of 2012, as well as touching on the issues raised in the previous post.

The three sections, indicated by the host’s questions in bold, canvass:

- Vietnam’s diplomatic triple-dealings with China, India and the Philippines in October 2011;

- The connections between great-power politics and Vietnamese ruling-party politics; and

- The difference between the Philippines’ and Vietnam’s approaches.

The interview was broadcast by the multilingual Australian SBS Radio with with Jie Chen 陈杰, Professor of International Relations at the University of Western Australia. Professor Chen is an expert on Southeast Asian and Chinese foreign policy who is supervising my PhD project.

Would China and Vietnam want a fight?

Posted: August 23, 2012 Filed under: China-Russia, China-US, China-Vietnam | Tags: 1988 Spratly Battle, Cam Ranh Bay, China-Vietnam relations, Gazprom, Johnson South Reef Skirmish, legitimacy, PLA, s, Sino-Vietnamese relations, south china sea, spratly islands, Truong Tan Sang, US-China relations, Vietnam-Russia 8 CommentsBill Bishop (@niubi) raised an important point in yesterday’s Sinocism:

economic problems in china, economic problems in vietnam. a skirmish in the south china sea might be a distraction and an economic fillip for both?

This is worth thinking through carefully, and i would be most obliged if readers could pick out the holes in my logic and knowledge.

My propositions are

- that China could benefit from such a fight, though it might be too afraid of US opportunism to grasp them; and

- even if China was indeed up for a fight, it would take both of them to tango, and Vietnam wouldn’t be keen.

China would be the likely beneficiary of a live-fire skirmish involving the PLAN, for under that pretext China could evict Vietnam from one or more islands of its choosing. That would be the first time the People’s Republic had ever controlled an island in the Spratly Archipelago.

Possession of a single island in the Spratlys would hugely enhance the position of the People’s Republic strategically, logistically, and legally. What is more, i dare say it might be viewed as a glorious success by some people in China.

“Retrieving” 收复 a Spratly island by evicting an opponent is perhaps the one action that could actually impress the Chinese public and bolster the party’s “nationalist legitimacy” at home.

Despite possessing a much better navy and air force than the Philippines, i think Vietnam would be a more appealing target for an island “retrieval” simply because there would be no issue of the US becoming involved via treaty obligation. This is also reflected in the fact that Vietnam is the only country the PRC has attacked in the South China Sea.

The best opportunity for the PRC to make a move like this would be a clear-cut instance of Vietnamese aggression. A flagrant attack a PLA Navy boat by Vietnamese fishermen might constitute a justfiable rationale for an island battle. If multiple attacks happened (or could somehow be made to happen) then China could instruct its military to go looking for the attackers on one or more of the Vietnamese-controlled Spratly Islands.

Would America step in to prevent China from gaining such prime a foothold as a Spratly Island? I think not, as long as China could convince the world that Vietnam had started the incident.

On the other hand, even if Vietnam were to oblige by recklessly attacking the PLA Navy, the risk for China would be that the US could use the ensuing PLA retaliation as an opportunity to assert itself in the region, and perhaps even to bring the PLA’s development “under control”. From my hypothetical Chinese military perspective, the US could conceivably unleash its considerable (though much-degraded by Saddam’s WMDs) narrative-building powers to convince the world that China was to blame for any clash — even, or perhaps especially, a clash brought about by Vietnam, under US encouragement.

So while China would stand to gain a great deal from a skirmish, it could still be deterred by its own belief in the US’s evil intentions and opportunism.

Vietnam, meanwhile, has its good friend Russia increasingly tangled up with its own fortunes through a range of energy development partnerships (“such as Vietsovpetro, Rusvietpetro, Gazpromviet and Vietgazprom”), and Russia may soon be present in Cam Ranh Bay, which Vietnam has offered as a the site of a Russian supply and maintenance base.

Xinhua’s Moscow-datelined report from August 27, ‘Vietnam declines to give Russia exclusive rights to naval base‘ (my emphasis) appears to be clutching at straws trying to find a positive angle for China; President Truong Tan Sang’s 5-day visit to Russia last month appears to have been a riproaring success. The reason Russia will not have exclusive rights, is of course that Vietnam has invited the US military to use Cam Ranh Bay too.

The Chinese media have frequently accused the US of trying to embolden China’s co-claimants into making provocations. From Hillary’s famous declaration of national interest, to (non-combat) military exercises in July 2011, to Leon Panetta’s visit to Cam Ranh Bay in June this year, the US has definitely been pushing things forward with Vietnam too.

In the event of a skirmish with China, however, Vietnam still couldn’t count on support from either the US or Russia, both of which continue to have enormous national interests in maintaining peace with the People’s Republic.

When it comes to the South China Sea, Vietnam is the only country that has ever actually tried to fight with the PRC there — and that did not end well (see video at top). Yet Vietnam’s position in the Spratlys remains very favourable compared to the People’s Republic’s, occupying at least six islands and more than twenty reefs and atolls, and an estimated 2,000 troops posted as of 2002. Why would they risk this, with possession is (probably) nine-tenths of the law?

To me, this all points to Vietnam being determined to avoid serious escalations, even as the US bolsters its position in the region.