Comparison of Vietnam and China’s joint statements, 2011-2017

Posted: February 3, 2017 Filed under: China-Vietnam, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, South China Sea | Tags: arbitration, China-Vietnam, China-Vietnam joint statement, China-Vietnam relations, joint communique, Nguyen Phu Trong, nine dashed line, nine-dash line, Philippines vs China arbitration, Sino-Vietnamese relations, south china sea, South China Sea arbitration, UNCLOS, UNCLOS and South China Sea, Vietnam-China joint statement 2 Comments

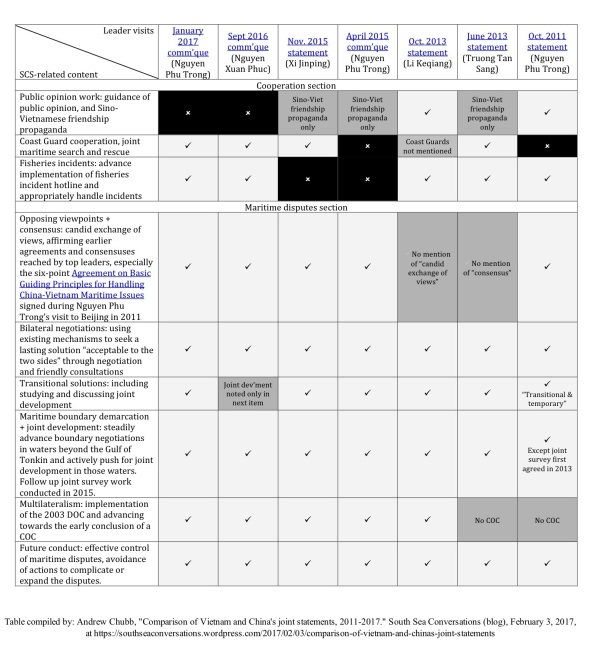

Comparison of Sino-Vietnamese joint statements since 2011 (click to enlarge). Links to sources: January 2017 communique (Nguyen Phu Trong visit to China); Sept 2016 communique (Nguyen Xuan Phuc visit to China); Nov. 2015 statement (Xi Jinping visit to Vietnam); April 2015 communique (Nguyen Phu Trong visit to China); Oct. 2013 statement (Li Keqiang visit to Vietnam); June 2013 statement (Truong Tan Sang visit to China); Oct. 2011 statement (Nguyen Phu Trong visit to China).

East Asia Forum has kindly published a piece from me on recent developments in Sino-Vietnamese relations. To supplement it, i’m posting here a table comparing the South China Sea-related elements of the last 7 joint statements between the two.

The comparative table was the basis for the article’s argument that General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong’s visit to Beijing last month did not involve any softening of Vietnam’s position on the issue.

According to a knowledgeable Vietnamese source, there are three types of Sino-Vietnamese bilateral joint statements issued after high-level meetings. In ascending order of importance these are:

- Joint press release (联合新闻公报, thông cáo báo chí)

- Joint communique (联合公报, thông cáo chung)

- Joint statement (联合声明, tuyên bố chung)

These documents are often not released in English, and some of the translations that have appeared have been incomplete or unreliable, so the table above compares the Chinese full text as published by state media (links are in the caption area above).

The table also includes an item, not discussed in the EAF article for space reasons, on cooperation in public opinion work. In the 2011 joint statement, the two sides pledged cooperation on “strengthening public opinion guidance and management” – which, in the context of several weeks of anti-China protests through the middle of that year, was tantamount to a Vietnamese undertaking to dampen anti-China sentiments.

Interestingly, however, there has been no analogous item in the recent joint documents — even after another, even more intense, wave of anti-China sentiments burst forth in 2014 during the HYSY-981 oil rig standoff. Its omission from subsequent documents might indicate an acceptance on China’s behalf of the strength Vietnamese nationalist sentiments that flow in its direction at times of heightened tensions. Perhaps also an acknowledgement that Hanoi is already doing what it can to promote Sino-Vietnamese friendship? Any other readings?

The EAF piece is reposted below. Based on some early feedback, i should have been clearer that in suggesting . . .

China may have pulled back from its pursuit of particular claims that have no basis in international law

. . . i do not mean the PRC has seen the light and is abandoning all claims deemed unlawful in the UNCLOS arbitration. Just that there are some unlawful aspects of China’s claims that it is no longer pushing, and this has removed some of the major drivers of Sino-Vietnamese tensions.

As always, further comments, arguments, additions and corrections are much appreciated.

========

Vietnam and China: contingent cooperation, not capitulation

East Asia Forum, February 2, 2017

Andrew Chubb

On 12 January, Vietnamese Communist Party General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong arrived in China for a lavish, well publicised four-day official visit.

Nguyen’s trip symbolised the significant improvement in Sino–Vietnamese relations since their nadir during the HYSY-981 oil rig confrontations in mid-2014. Hanoi’s subsequent suppressionof nationalist protests marking the 19 January anniversary of China’s eviction of South Vietnamese forces from the Paracel Islands in 1974 has since confirmed the relative health of ties between the two party-states.

But linking Nguyen’s trip into a narrative of Southeast Asian countries allegedly acquiescing to Beijing’s claims in the South China Sea would be misleading. Rather than a Vietnamese tilt towards China, the visit was a continuation of recurring features of the bilateral relationship, amid improving ties underpinned by the moderation of some of China’s policies.

Over the past few years, official visits by party and state leaders have been a regular feature of Sino–Vietnamese relations at all but the worst of times. Each trip has concluded with detailed bilateral statement, so a basic idea of the significance of the 2017 visit can be gleaned by comparing the joint communique it produced against earlier documents of this type.

One salient change was the ‘close and friendly’ atmosphere that the communique said prevailed through Nguyen’s meetings. By comparison, it has usually been ‘friendly and candid’ since 2007–2008, when China’s policy in the South China Sea became more assertive. This implies the general state of relations is now equivalent to that which prevailed in the early to mid-2000s when the description was often used.

Secretary Nguyen’s trip did not mark any major change or softening in Vietnam’s position on the South China Sea issue. It did, however, continue the revival of maritime crisis management and confidence-building initiatives — such as Coast Guard exchanges and a fisheries incident hotline — whose progress appears to have stalled after the HYSY-981 incident.

While the joint statements from leaders’ visits in 2011 and 2013 included a call for ‘calmness and restraint’, this language has been absent from more recent documents. This suggests the two party-states consider the present level of tension in the disputed area to be lower. It also implies a mutual recognition of each other’s policy status quo as basically rational.

A further sign of the reduced tensions on the water is that the most recent communiques have called for implementation of the 2003 Declaration of Conduct for the South China Sea, and pursuit of a Code of Conduct before affirming the need for ‘control of maritime disputes’. Previous documents back to 2013 had placed this before the multilateral agreements — the 2011 joint statement did not even mention the DOC.

Hanoi’s symbolic declarations of cooperation with China have often been accompanied by substantive cooperative initiatives with China’s rivals, and the 2017 meeting was no exception.

While the Vietnamese Communist Party’s General Secretary received red-carpet treatment in Beijing, then-US secretary of state John Kerry was in Hanoi, witnessing the 13 January signing of two heads of agreement between ExxonMobil and Vietnam’s state oil company PetroVietnam over a major undersea gasfield straddling the PRC’s nine-dash line. Beijing has previously issued warnings to Exxon over its participation in the project, which is now estimated to contain 5.3 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. The latest plan will see the US multinational build an 88-kilometre undersea pipeline, carrying gas to the Vietnamese mainland by 2021.

The day after Nguyen concluded his China trip, Vietnam welcomed Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to Hanoi. Standing beside Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc, Abe announced Japan would provide six new patrol vessels on low-interest development loans to ‘strongly support Vietnam’s enhancing its maritime law enforcement capability’. These white-hulled capabilities have been central to China’s advances in the disputed areas in recent years, so it was an announcement with both symbolism and substance.

Similarly, when now-Premier Nguyen Xuan Phuc was in Beijing in September 2015, General Secretary Nguyen was in Tokyo securing secondhand maritime patrol boats, along with Japanese criticism of land reclamation in the South China Sea. This pattern has been apparent since at least 2011. During General Secretary Nguyen’s October 2011 trip, Chairman Truong Tan Sang was visiting India, strengthening military training exchanges, confirming Indian access to the Nha Trang port, and negotiating to purchase BrahMos cruise missiles. Indian and Vietnamese state oil companies also signed deals covering disputed areas of the South China Sea.

Vietnam’s highly conspicuous hedging appears designed to signal to Beijing that its cooperation does not imply acquiescence, but is rather contingent on China’s own conduct.

Indeed, Chinese policy in the South China Sea is probably the most important determinant of the state of bilateral ties. Since 2000 at least, the frequency and warmth of the leaders’ communiqués has tended to correlate – negatively – with the pace of China’s assertive advances in the disputed area. Consistent with this pattern, China has moderated its conduct in some important ways in recent months.

Some adjustments to Chinese policy have, for the time being at least, brought Beijing into partial compliance with the 2016 ruling of the UNCLOS-mandated arbitral tribunal. Despite its surface-level bluster rejecting the process, the PRC has, for example, eased its harassment of Philippine fishers at Scarborough Shoal, allowing them access to the fishing grounds within the atoll’s lagoon.

One of the key sources of Sino–Vietnamese maritime tensions since 2007 has been the PRC’s assertions — verbal and at times physical — of oil and gas rights across the area within the nine-dash line. This was another of the key elements of China’s policy that was deemed unlawful by the UNCLOS arbitral tribunal.

But shortly after the ruling, a new and detailed interpretation of the nine-dash line, published in the military’s official newspaper, appeared to decouple the line from claims to energy resources. That Beijing has so far refrained from publicly criticising the above-mentioned Exxon–PetroVietnam offshore gas project further suggests China may have pulled back from its pursuit of particular claims that have no basis in international law.

The removal of this major driver of Sino–Vietnamese tensions offers the most compelling, but also easily overlooked, explanation for the recent warming of bilateral ties.

Andrew Chubb is a PhD Candidate at the University of Western Australia. You can follow him on Twitter at @zhubochubo.

This is really useful, thanks for digging into it. The teeniest of pedantic corrections. Because so many Vietnamese (about half the population) have the family name Nguyen, and a few other family names cover most of the rest, it’s usual to reference Vietnamese by their given name. So Nguyen Phu Trong becomes ‘Trong’ on subsequent references. That’s about as much as I can add to this!

Cheers Bill

>

Thanks Bill, will definitely take up that suggestion