Luconia Breakers: China’s new “southernmost territory” in the South China Sea?

Posted: June 16, 2015 Filed under: China-ASEAN, China-Malaysia, CMS (China Maritime Surveillance), South China Sea, State media | Tags: ASEAN and South China Sea, 《中国国家地理》, China Coast Guard, China Coastguard, China-ASEAN, China-Malaysia relations, Chinese foreign policy, Chinese National Geography magazine, 琼台礁, 马宏杰, Gugusan Beting Patinggi Ali, Hempasan Bantin, James Shoal, Luconia Shoal, Luconia Shoals, Ma Hongjie, Malaysia, Malaysia and South china SEa, normalized patrols, North Luconia Shoal, PRC foreign policy, PRC maritime law enforcement, Shahidan Kassim, Shan Zhiqiang, south china sea, South Luconia Shoal, Spratly, spratly islands, Wu Lixin, 单之蔷, 吴立新, 曾母暗沙 13 Comments

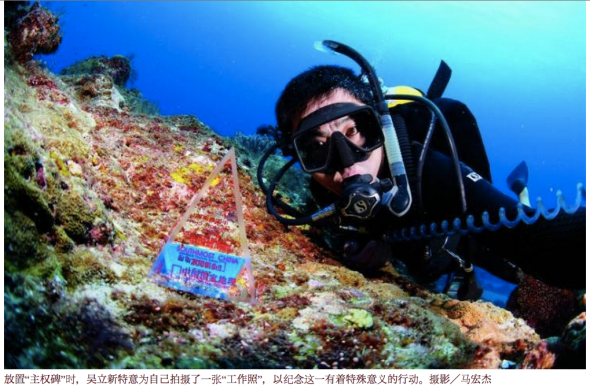

The “island” at Luconia Breakers 琼台礁/Hempasan Bantin (source: Chinese National Geography, October 2010)

In a vivid illustration of how dynamic the status quo in the South China Sea can be, an apparently new Spratly island, formed by the forces of nature, has become a source of tension between China and Malaysia.

Luconia Breakers (Hempasan Bantin / 琼台礁) is just over 100km north of James Shoal, the shallow patch of ocean that Chinese people are routinely taught is the southernmost point of their country’s “territory“, despite it being several metres underwater.

As this post will show, unlike James Shoal, the territory at Luconia Breakers actually exists above the waterline. This is significant because if the PRC ever needs to clarify the nature of its maritime claims under international law, it could end up adopting the “new” feature as its southernmost territory.

Topping off the intrigue, the train of events leading to the current Sino-Malaysian standoff may well have been set in motion by an adventurous Chinese magazine team.

.

A polite but serious standoff

Although Malaysia and China both claim sovereignty over several territorial features and maintain overlapping resource rights claims over thousands of square kilometres of maritime space, they generally avoid any outward shows of confrontation as they pursue a “special relationship”. Malaysia, as Prashanth Parameswaran describes it, runs a policy of “playing it safe“, while the PRC makes minimal fuss over the numerous active Malaysian oil and gas fields, infrastructure and even tourism operations within the nine-dash line.

Hints of Malaysian dissatisfaction with China’s actions have, however, been getting clearer and more frequent in the past couple of years. It was discernible in the ASEAN expressions of collective “serious concern” about land reclamation at two meetings chaired by Malaysia this year, and last year following the PRC’s deployment of an oil rig to disputed waters last year. Other examples include publicly announced diplomatic representations over Chinese activities at James Shoal, and upgrades to military hardware and facilities bordering the area.

The latest data point emerged on June 3, when Malaysian newspaper the Borneo Post reported:

China has been detected encroaching on Malaysian waters at the Luconia Shoals, which are known as Gugusan Beting Patinggi Ali, located just 84 nautical miles from the coast here.

The same day Shahidan Kassim, a minister who oversees the Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agency, posted a collection of pictures on his Facebook page showing a Chinese Coast Guard ship and a stony cay sitting well above the waterline.

Shahidan’s Facebook post stated that Malaysian naval and maritime enforcement ships were anchored within 1 nautical mile of the Chinese vessel. Since then Malaysia’s navy has reportedly deployed a guided-missile corvette to the area to back up the vessels already monitoring the Chinese government ship. In a later interview with local media, Shahidan said the issue involved sovereignty and would therefore be dealt with at the cabinet level. It appears, in short, to be a polite but serious standoff. So, what is the issue at stake? What and where are the Luconia Shoals?

.

Where and what are the Luconia Shoals?

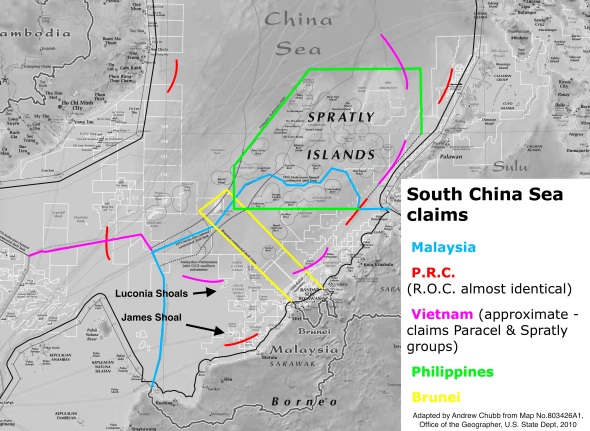

The Luconia Shoals, North and South (北康暗沙 and 南康暗沙), are two groups of mostly underwater features at the southern end of the South China Sea. As a stark reminder of the vast sprawling area the Spratlys cover, these shoals are more than 440km from Fiery Cross Reef, the heart of China’s island-building frenzy. The above-water reef in the pictures is at Luconia Breakers, which is at the southern end of the group, about 150km north-north-west of Borneo.

Being so distant from the areas of intense competition to the north, the Luconia Shoals are something of a new frontier for even many long-time South China Sea watchers. They are not even mentioned in one of the major English-language lists of geographical features in the Spratlys. As the map above indicates, they are claimed by both China and Malaysia — thankfully, this is probably just a bilateral dispute since Vietnam does not appear to maintain claims this far south, though i haven’t confirmed this.

The micro-island at Luconia Breakers, pictured in the photographs above, is not listed as being above the waterline in many credible sources of information on the Spratly Islands. The US State Department’s gazetteer of 168 Spratly features does not list it among the features “visible at high tide”, while a study based on old British surveys specifies that it is the only reef in the South Luconia Shoals to “dry”. Another source states that there is “no emergent land at Luconia Shoals”.

Certainly the Malaysian official Shahidan seemed to suggest the emergence of land here was a recent development, according to the Borneo Post report (emphasis added):

He explained that one of the areas within [Luconia Shoals] had become a small island, which resulted in many parties being interested in it, possibly with the intention of encroachment.

As we will see below, available evidence confirms the conclusion that it is in fact territory above the waterline at high tide.

.

Chinese Nationalist Geography

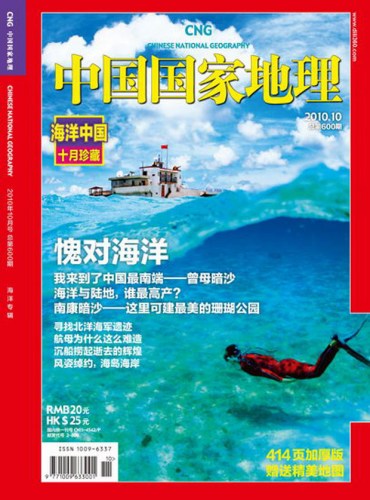

In mid-2009, a Chinese editorial writer and two photographers made an extraordinary voyage to explore the southern limits of the nine-dash line. The trio worked for Chinese National Geography 中国国家地理I, the flagship PRC geography magazine published since 1950 by the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Geographical Society of China. The title might be more accurately translated as Chinese State Geography.

The team were not just heading out to document the coral formations and undersea life of these remote shoals; they also carried “sovereignty markers” to proclaim China’s ownership. But their role in advancing PRC state sovereignty in the South China Sea may have ended up going much further than this, for they “discovered” a new southernmost land territory.

Chinese National Geography photographer Wu Lixin takes a selfie while at work installing “sovereignty marker” on James Shoal, May 1, 2009. (Source)

First of all, credit where credit is due. The three patriotic geographers, Shan Zhiqiang, Wu Lixin and Ma Hongjie, performed a truly epic feat of reporting. They gained access to one of the most remote and mysterious corners of a remote and mysterious archipelago, a couple of days out into the ocean, using rickety private transportation. Not only this, they brazenly did this by using Malaysian boats, while basing themselves out of Malaysia, China’s rival claimant to these territories!

As is abundantly clear in the excerpt translated below, Shan and his colleagues were fired more by the flames of narrow nationalism than any commitment to professional objectivity, environmental concern or world peace, but you have to tip your hat to their determination and intrepid spirit.[1] Their exploits produced not just one but several cover stories in a 600-page special issue of the magazine devoted to China’s maritime space published in October 2010.

After flying to Malaysian Borneo from Kuala Lumpur, they pose as recreational fishermen, hiring a local boat to take them to James Shoal on April 30. During that two-day trip the local skipper mentions there is land above the surface of the water at Luconia Shoals. Editor Shan asks him to take them there but the boat doesn’t have the range to make it there and back. After a visit to Malaysia’s diving resort at Swallow Reef, they find a larger boat with a four-man crew, and set off on another ostensible fishing expedition, this time encompassing the Luconia Shoals.

Here is the part where they “discover” the island at Luconia Breakers, the following day:

In the afternoon the boat heads for another reef, this time in the South Luconia Shoals — Qiongtai Reef [Luconia Breakers]. I imagine it will be another like Nanping Reef [南屏礁], an underwater atoll.

…’There’s an island ahead,’ says [photographer] Wu Lixin suddenly.

I don’t believe him — we came here to look for China’s southernmost land, but the entire voyage so far has been a disappointment [with no sign of dry land]. But here on the horizon there is a spot of white. Wu runs up the stairs and takes out a telescope.

‘It’s really an island,’ he says. The boat heads in the white dot’s direction. So Qiongtai Reef is actually a miniature island above the waterline, surrounded by a reef. Might this be the southernmost above-water Chinese territory we have been searching for? Yes. Looking at the map, it appears so.

The water turns that jade-green hue that indicates it’s getting shallow. The boat stops; it can’t go any further. Looking across the water, the green-coloured area appears to be ring-shaped, meaning this is another coral atoll. The difference is there is a little island in the middle of this one. From a distance it is white. I’m extremely excited, as this beyond our expectations. This kind of formation is called a grey-sand island, formed by storms piling up fragments of dead coral.

…We can only get to the island in a dinghy, which is lowered into the water from the main boat. We get in and set off. At one point we stop for [underwater photographer] Wu Lixin to dive in. Only after noting the GPS coordinates do I let the fat crew member continue to drive us towards the island. As the dinghy accelerates forward, a school of flying fish emerges.

…The next 1-2 kilometres is all underwater gardens. Everything else aside, I think this atoll, this islet, this expanse of coral sea is incomparably valuable, and it’s worth Chinese people proclaiming sovereignty over, and building it into a Chinese Spratly coral national park to be permanently protected. This may well be the Chinese people’s best diving spot, and could become the place where our descendants get to know coral, tropical fish, molluscs, and all kinds of tropical marine life. Can this wish of mine be realized?

The water is getting shallower, and the dinghy is now hitting the bottom. We get out, and the water is only up to our knees. Beneath our feet are fragments of coral skeletons. The islet is in front of our eyes.

We quickly make landfall. All around us are pieces of white coral, which makes a crunching sound with every step. These coral fragments are piled up into a hill about 8 metres high. This is the height now, at 4pm on May 8, 2009, which is low tide, so the island seems particularly large. There is a horizontal line dividing the island into two sections: one dry and white, the other wet and brown. This is the high-tide line, and it shows there is about 3-4 metres’ difference between the water level at the two extremes.

On the island we see traces of humans — a spoon, a bag, and some plastic water bottles dumped by the tide. The most prominent is a large, pyramid-shaped concrete block that appears to be there for political reasons, being in the shape of a sovereignty marker. There is no writing on it, or perhaps the words have been worn away. It would not have been easy to get this concrete tablet here.

According to Shan, when the photograph above was taken, his GPS indicated an elevation of 9 metres above sea level.

Shan’s enthusiasm for the marine environment is palpable, in a terrifying way. In one sentence he waxes lyrical about the stunning natural beauty of the place before citing this as a reason to assert Chinese sovereignty, a process that implies the exclusion of all other state agents and the likely militarization of the area — which would be a downright hideous result for the marine environment. Several times in the piece he even proposes filling in parts of the atolls he so admires, to create a tourist attraction like Malaysia’s dive resort at Swallow Reef. The stated motivation is national aggrandizement:

although parts may be underwater, it only needs some reclamation and infill to easily be made into an artificial land area and to create airstrips, like Swallow Reef. We Chinese absolutely have the capability to plant our feet firmly in the Spratlys, and these atolls are our foothold and a space of hope for the future.

The piece ends with a final ironic kick: when they arrive back at port, the boat’s owner comes to meet them:

He even drove a small truck for us, saying it was to transport the fish we had caught. We had told him all along that we were going there to fish, so he thought we would have caught a lot. We sheepishly told him we were novices and didn’t know how to fish, and that next time we would definitely not leave him disappointed.

Shan Zhiqiang was at the time Editor-in-Chief of the Chinese National Geography Editorial Department 编辑部主编. He has since been promoted to Executive Managing Editor 执行总编 of the magazine publishing house.

.

China’s southernmost territory?

Recapping the significance of the voyage at the end of the Chinese National Geography article, Shan emphasized the likelihood that they had discovered China’s southernmost land point:

Most importantly, Qiongtai Reef may be China’s southern extremity — the southernmost point that has dry land. Unless an ice age comes [making] James Shoal protrude above the water…at present, Qiongtai Reef is probably the southern extremity of China’s land 中国陆地的最南端.

In this video, Shan says that after they returned, the team consulted with experts from the State Oceanic Administration (SOA), who confirmed that this was indeed the case.

There are several reasons agree with this assessment that the island at Luconia Breakers is in fact a high-tide elevation, and therefore the most southerly object of a Chinese territorial claim:

- The colour bands visible in the photographs almost certainly indicate water levels (are there any other explanations?) The top section is bright white, strongly suggesting it stays dry.

- When Shan and his colleagues arrived at low tide, he estimated the height of the “island” at 8 metres, and reported his GPS’s figure of 9 metres. This is consistent with the sailing information sources i’ve looked at, which specify tides up to 4-5m in this area.

- Shan says a Malaysian fishermen’s mention of the possibility of dry land at Luconia Shoals was the whole reason his team made the trip out there. Politically, there is no reason for Shan to make this up.

- The US National Geospatial Intelligence Agency’s sailing directions describe Luconia Breakers as “dry and on which the sea breaks heavily”. No further details are given.

- Google Earth imagery also shows the “island”. Note the shape of the dark patches enveloping the island on three sides, which are visible in Shahidin’s Facebook photos above. The satellite image was taken earlier this year:

A magazine article is obviously not an official claim to sovereignty. Unlike the article on James Shoal in the same issue of the magazine, there are no mentions of sovereignty markers being dropped at Luconia Breakers, though this hardly rules it out.[2] Nor does the piece state that his group explicitly proclaimed Chinese sovereignty over the “island” (this is of course strongly implied). The editors and censors — presumably including Editor Shan himself — appear to have been wary of the sensitivity of sovereignty claims, as the piece does not once use the term “territory 领土”, in every instance referring instead to “land 陆地”.

Nonetheless, if it is indeed the southernmost high-tide elevation within the nine-dash line, then it’s likely to become China’s southernmost territorial claim in the future, should the PRC ever clarify what it is claiming under international law (Baidu Baike already ascribes it this status). The Chinese National Geography article’s “discovery” strongly suggests the PRC authorities were not previously aware of the island’s existence — if they were, they never made this known even to their top state-run geography media. If it’s a new, naturally formed island then it will be interesting, to say the least, to see how China would advance a claim of “historical” sovereignty over it.

.

Recent developments

The PRC’s stationing of Coast Guard ships around Luconia Breakers is a major development in the South China Sea disputes. It marks the first known extension of “normalized 常态化” Chinese patrolling — meaning the maintenance of a constant presence in a given area — into a Malaysian-controlled area of the sea. Normalized patrolling has previously been seen from 2012 onwards around the Diaoyu Islands, Scarborough Shoal and Second Thomas Shoal, but in those cases the targets have been the Philippines or Japan, and the actions taken at times of heightened tensions. In this case the target is Malaysia, a country with whom Beijing has maintained much warmer relations, and the area in question is even further from the Chinese mainland.

Chinese maritime officials have alluded to the rollout of this new policy in public statements. Patrols of the Luconia Shoals began in August 2013, and in January 2014 the SOA announced it would “reinforce” patrols there throughout the course of the year. In mid-2014 then-SOA Party boss Liu Cigui called for

strengthening China’s on-water normalized 常态化 presence, continuing to consolidate the results of special-action rights defense law enforcement in the Diaoyu Islands, Scarborough Shoal, Second Thomas Reef and the North and South Luconia Shoals.

In February 2015 the SOA’s new Party Chief, Wang Hong, delivered a report on maritime work in 2014 that stated the Coast Guard had been “on duty 值守” at Luconia Shoals and Second Thomas Reef throughout the previous year.

The Malaysian response has been at least as significant. The uptick in public criticisms and diplomatic protests[3] against Beijing’s conduct has coincided with the PRC’s rollout of “normalized” patrols, and the response has gone well beyond increased verbal frankness. As noted above, in his Facebook post, Minister Shahidan stated that Malaysian Navy and Maritime Enforcement Agency ships were, as of June 3, positioned within 1nm of the Chinese ship. More recently, on June 11, an anonymous Malaysian “spokesman” confirmed that the Royal Malaysian Navy had sent a guided missile corvette to the area to coordinate with maritime law enforcement ships.

There are many productive Malaysian oil and gas platforms in the area around Luconia Shoals, connected to pipelines which send back energy to help power the states of Sarawak and Sabah. This critical energy security factor makes it unlikely Malaysia would be willing to back down and allow the PRC to maintain its presence unopposed. Notably, in contrast to his remarks on Scarborough Shoal, SOA boss Wang did not declare that China’s “normalized” presence had achieved “administrative control 管控” of the Luconia Shoals. This may reflect Malaysia also maintaining a near-constant presence there to monitor China’s activities.[4]

Since the Chinese operation at the Luconia Shoals began, there have been Malaysian joint military exercises with the US and discussions on possible hosting of maritime surveillance flights, announcements of upgrades at a nearby naval base, and increased Malayisan cooperation with Vietnam and the Philippines. Shahidan even said he had recommended Malaysia’s Tourism Ministry create a plan to develop tourism in the area, just as the Chinese National Geography reporter had urged his superiors in Beijing to do.

Opposition MPs are using the issue to criticize the government, and the Malaysian media seem to be keenly pursuing information on the issue, but the tougher stance towards China seems to be coming right from the top. Prime Minister Najib, in an April interview with the state news agency Bernama, came close to naming China when he said the issue “should have consultation without the show of force or raising tensions or any force tactics against smaller countries” [emphasis added]. Clearly he wasn’t referring to the United States. The country’s Armed Forces Chief General Zin also said at this year’s Shangri-La Dialogue: “We do not know what they are trying to do [in the South China Sea] . . . It would be good if China can come out publicly and announce what they are doing.”

So why might China be doing this? It’s very hard to see the PRC’s actions here as the result of uncoordinated policy. The SOA officials’ comments canvassed above were all made in national-level reports and speeches, and their references to the Luconia Shoals operation were specific and terse. This provides little support for the idea that sub-state actors may be using such assertiveness to advance bureaucratic interests. Additionally, the China Coast Guard ship photographed at the reef (#1123) is from the agency’s North Sea Branch, but the area falls in the South Sea Branch’s area of responsiblity, which strongly supports the conclusion that the maintenance of constant presence there is a centrally-coordinated project.

If it is as coordinated and intentional as this would suggest, is it a tactical error from China? With relations with Vietnam, the Philippines and Japan all tense as a result of the maritime disputes, this has opened up a new front, even further from the PRC homeland, while at the same time raising the stakes with one of Southeast Asia’s swing states in a year in which it has the rotating ASEAN chairmanship. What am i missing here? Could it be that Malaysia’s position within ASEAN was always closer to Vietnam and the Philippines than we thought, so the PRC has correspondingly less to to lose from provoking Malaysia? Is it related to the improvement in relations with Japan over the past 18 months? Or could it in fact be a different tactical game, aimed at undermining ASEAN under Malaysia’s chairmanship by sharpening the divisions between claimants and non-claimants? I’d love to read any answers or other thoughts in the comments below.

We also can’t know for sure whether the PRC’s newfound focus on the Luconia Shoals is related to the magazine team’s “discovery” of a micro-island there. But interest presupposes awareness, and awareness of the reef’s territorial identity was evidently lacking before their epic voyage uncovered a less illusory “southernmost territory” than the one currently enshrined in China’s textbooks.

—

[1] English-language media reporters traditionally almost never make it to the Spratlys, though there have been some outstanding feats of reporting from the Spratlys in recent years. Brilliant freelancers Ashley Gilbertson and Jeff Himmelman created the New York Times’ infographic ‘A game of shark and minnow’ in 2013. ABC TV’s Eric Campbell also made a largely unnoticed but highly enlightening journey to the Spratlys last year. But these trips, like their rare predecessors, involved being shown around by claimant militaries (the Philippines is the most open), and as a result, they focused mainly on the main disputed parts in the central and northern parts of the archipelago where the disputant states have their outposts – locations where limited imagery is already available.

[2] On the other hand, in this video Shan states that the team did not realize at the time that they were landing on “China’s southernmost land point”.

[3] It seems to be a Malaysian convention that diplomatic protests against China are announced before, not after, they are submitted — perhaps offering the other side a final chance to make proactive remedial efforts before it becomes formal.

[4] Some Chinese online sources quoted in English-language reporting, claim the area around Luconia Breakers has been under China’s “control 掌控” since mid-2014, but this claim is surely inaccurate. For one thing, the same sources say Malaysia has maintained a constant presence alongside the Chinese ships, which means it is equally in “control” of the feature. In addition, the term used in the posts, “control 掌控”, is not among the PRC agencies’ standard terminology for describing their policies around maritime features — instead, they use “实际控制” (actual control), “有效管理” (effective administration), and “管控” (administrative control). The sources are more credible when they describe a “normalized 常态化” presence of Chinese ships at Luconia. This is a term the PRC agencies have used to denote constant presence of patrol ships in the area, such as in the wake of the Diaoyu purchase, and the Scarborough Shoal standoff.

Lots of questions,without clear answers. What would be the basis for China’s claim of sovereignty over the atoll or rock in the Luconia Breakers? If the feature falls within the nine-dash line, China might claim it as part of its “blue water territory.” But as knowledgeable readers know, UNCLOS does not recognize “blue water territory” claims to the high seas. And while China asserts historical sovereignty over the Spratly’s, this feature is new. There’s very little, if any, “history.” China cannot claim its eunuchs, fishermen or officials ever visited the feature, unless they could dive, that is. Alternatively, China could claim to have “discovered” the feature, but the journalists found another nation’s marker when they arrived. If that is correct, how could China claim “discovery?” Wouldn’t the fact the new feature arose within Malaysia’s EEZ help give Malaysia the superior claim? Not that legalities mean anything to Beijing.

Finally, China’s dispute with Malaysia heats up while its disputes over the artificial islands cool down. China just announced it is within days of completing reclamation. Coincidence?

This is absolutely fabulous! Another magnificent contribution to the absurdist history of the South China Sea. I am trying to get comment from contacts in Malaysis – I’ll let you know.

Cheers

Bill

>

[…] Chubb, “Luconia Breakers: China’s New ‘Southernmost Territory’ in the South China Sea?” South Sea Conversations, 16 June […]

[…] of which have been used to buttress new footholds at Scarborough Reef, the Second Thomas Shoal, the Luconia Breakers, and the Senkaku Islands, and underwrite economic activities in disputed waters, most notably the […]

[…] decide who can and cannot occupy land. With Scarborough Shoal, the Second Thomas Shoal, and now the Luconia Breakers, China has used maritime law enforcement ships to achieve these ends nonviolently, daring other […]

[…] who can and cannot occupy land. With Scarborough Shoal, the Second Thomas Shoal, and now the Luconia Breakers, China has used maritime law enforcement ships to achieve these ends nonviolently, daring other […]

[…] Read more: https://southseaconversations.wordpress.com/2015/06/16/luconia-breakers-chinas-new-southernmost-terr… […]

[…] 16. “Luconia Breakers: China’s New Southernmost Territory in the South China Sea?” South Sea Conversations Blog, June 16, 2015, https://southseaconversations.wordpress.com/2015/06/16/luconia-breakers-chinas-new-southernmost-terr…. […]

My ancestors from sabah already knew those islands off sabah that can be seen from the coast as belonging to china.

But nowadays historical significance is irrelevent. Ability to protect and administer them is more important.

Best approach is to allow chinas need for first line defence amd shared interest in natiral resourses . A win win synergy.

Another option is ally with usa with high possibility of sparking a war within your own backyard.

[…] 2010, a group of journalists from China’s state-run geography magazine made an epic voyage (on a Malaysian boat) to the most southerly part of the Spratly Islands. In the long, lavishly […]

[…] 2010, a group of journalists from China’s state-run geography magazine made an epic voyage (on a Malaysian boat) to the most southerly part of the Spratly Islands. In the long, lavishly […]

[…] 2010, a group of journalists from China’s state-run geography magazine made an epic voyage (on a Malaysian boat) to the most southerly part of the Spratly Islands. In the long, lavishly […]

[…] 2010, a group of journalists from China’s state-run geography magazine made an epic voyage (on a Malaysian boat) to the most southerly part of the Spratly Islands. In the long, lavishly […]