“The whole world’s Chinese people are going”: decisive moments, and the perils of Diaoyu nationalism

Posted: August 19, 2012 Filed under: China-Japan, CMS (China Maritime Surveillance), Comment threads, Diaoyu, FLEC & Ministry of Agriculture, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, PRC News Portals, State media, Weibo | Tags: anti-Japanese protest, Chinese nationalism, demonstrations, Diaoyu, Diaoyu activists, 钓鱼, 警车被砸, Hong Kong, imagery, Japan Coast Guard, nationalism, pincer attack, Qifeng-2, Senkaku, 日本船夹击 4 CommentsLocated to the northeast of Taiwan, just under halfway to Okinawa, the Diaoyus have been controlled by Japan since the first Sino-Japanese War in 1895. China (both of them) claims that the islands were imperial Chinese territory before that, so Japan’s annexation of them in 1895 was an illegal land grab, and that they should have been returned to China at the end of WWII under the Potsdam Declaration.

The Diaoyus are not tiny coral atolls like the Spratlys and Paracels. They are (well, five of the eight features) genuine islands, albeit barren and uninhabited. Like the South China Sea islands, however, there’s believed to be black-gold in their bellies.

While the competition for the oil and gas resources can basically explain the two sides’ determination to claim sovereignty, on the Diaoyu the influence of nationalistic public opinion on the Chinese government’s behaviour appears more significant than on the South China Sea. To begin with, the public ill-will on both sides is deep-seated and getting worse, and political opportunists have the opportunity and motive encourage and exploit this.

The ICG’s Stephanie Kleine-Ahlbrandt recently commented that the leaders of China and Japan have little “political capital” to spend on defying “nationalist or populist sentiment”. In this excellent interview, SKA identifies nationalist sentiment as a constraint on governments’ ability to compromise or back down during a dispute. There are counter-examples where Chinese and Japanese leaders have appeared to defy pressure to be uncooperative and confrontational, such as Noda’s government’s speedy release of the recent protagonists, and China’s decision not to send patrol boats to guard them. But the two countries’ recent record suggests this has been difficult at times in the past.

Public opinion offers an explanation for what learned observers consider to be China’s counterproductively hardline stance in the previous Diaoyu confrontation in September 2010 (itself a response to Japan’s abnormally trenchant action in detaining an infringing Chinese fishing boat captain for several weeks rather than releasing him swiftly, as they did yesterday). And the ill-will on the part of both publics may have had a lot to do with the non-implementation of a deal negotiated back in 2008 for cooperative development of some of the oil and gas deposits in the area.

Nationalist activists on both sides are true believers in their cause, so even where their actions may be deliberately incited and/or tacitly sanctioned by their governments, they nonetheless impact the dispute by necessitating responses from the other side. Once the Qifeng-2 escaped the clutches of the Hong Kong police and sailed beyond the reach of the PRC authorities, for example, Beijing had little or no control over whether the passengers of the Qifeng-2 would actually manage to set foot on the island last Wednesday.

At the same time, the PRC government has on numerous occasions proved willing and capable of preventing Diaoyu activists from making their journey in the first place, whether in Hong Kong or on the way to the Diaoyus. This suggests that where Chinese citizens’ action has an impact, a decision to allow this must be made at some level of leadership — which could be made as low as a local PRC Coastguard official, a China Maritime Surveillance branch commander or as high as the Politburo Standing Committee.

Such decisions have certain easily foreseeable outcomes (a diplomatic incident of some kind was almost inevitable once the Qifeng-2 left PRC-controlled waters) yet their exact consequences in international politics are unpredictable. Moreover, these leadership choices occur in a domestic political context, which in China includes not only party politics and ideology, but also domestic nationalist discourse — what groups of people are thinking about where the country is or should be going.

The recent episode illustrates vividly what a dynamic and contested process of simultaneous group interpretation and elite engineering ‘nationalism’ really is.

Chinese activists jump from the Qifeng-2 onto Diaoyu Island, carrying PRC and ROC flags, August 15, 2012.

Take the above photo, for example — taken at the critical moment when the activists jumped ashore. Is the ROC flag something to be proud of, or ashamed? Is its appearance here a symbol of Chinese unity or division?

Weibo’s microbloggers appeared to see it more as a sign of cross-straits collaboration, enthusiastically forwarding it around as proof that the activists had made it onto the island. According to Weiboscope, it was at time of writing the most-forward image of the incident.

The PRC internet authorities also don’t seem to object to its dissemination, intact, on Weibo and other online news sources (see here and here). In stark contrast, however, the propaganda authorities overseeing China’s print media clearly saw it very differently to the online public, for among China’s main newspapers the ROC flag was either cropped out, crudely paint-bucketed red, or otherwise blotted out in very nearly every instance (among hundreds of covers on Abbao i found only one exception, the obscure Yimeng Evening News). The same was the case on mainland TV.

This might have had something to do with the gloating the official media have recently been engaging in over the fact that a group of Diaoyu activists from Taiwan last month waved a PRC flag to proclaim sovereignty from seas near the islands — even though they got an escort from the ROC Coastguard.

There was also perhaps the inconvenient fact that this time around the ROC authorities had pressured local activists into abandoning their trip and refused all but the most elementary assistance to the Qifeng-2 when it tried to stop past on its way from Hong Kong to the Diaoyus. According to the Global Times (English):

Earlier on Tuesday, the ship anchored in the waters near Taichung, after the local marine authority denied their application to reach land. The activists were only able to procure limited freshwater supplies.

The news on Tuesday that activists from Fujian who had wanted to join the expedition had canceled their plans due to “reasons of weather and procedure” also raised the question of exactly which of the ‘three regions’ (Taiwan, Hong Kong and the PRC) actually represents the Chinese people best. The top comments on Phoenix’s 111,000+ participant thread for ‘Mainland activists cancel trip to Diaoyu, citing weather and procedures‘:

“I know the reason you can’t go, I understand, backup is lacking, speechless.” [11,790 recommends]

“Clearly a crock of shit. Whoever believes it has got water in their brain.” [8166]

“Such a loss of face………speechless. Support the Hong Kong and Taiwan compatriots.” [5157]

“The whole world’s Chinese people are going, it’s just the mainland…” [4291]

Once again, the idea of the PRC government’s rule being based on anything that can be usefully understood as “nationalist legitimacy” appears questionable. And the idea that the party-state is trying to build up such “nationalistic legitimacy” via its foreign policy actions looks patently absurd.

On the topic of absurdity and Hong Kongers’ Chinese patriotic credentials, Kong Qingdong didn’t escape the participants of the Tencent thread above:

“This is the Hong Kong people that Kong Qingdong said are running dogs! Is he cross-eyed?” [17,489]

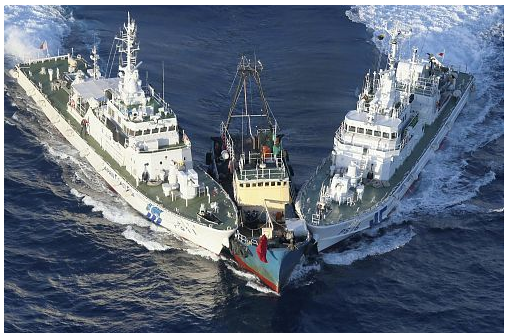

The other widely-circulated decisive-moment photograph from the scene of the confrontation further illustrates how deficient in nationalistic credentials the PRC state is:

This stunning image cast the Chinese activists in an intensely helpless position. When i first saw it i couldn’t believe that it was real; Photoshop-wielding nationalist students wanting to raise a rabble could hardly have done better. Taken by a Japanese photographer for the Yoimuri Shimbun, it makes the two Japanese Coastguard boats look positively evil.

That’s probably why it has been placed on newspaper covers all over China (once again, Abbao can illustrate), and pumped around the internet by the People’s Daily website’s Weibo account.

But it also rams the viewer with an almost unavoidable question: why was no-one there to help?

The giant comment threads on the portals indicate that exactly this kind of question is in the forefront of many ordinary PRC people as they read the news on the internet.

Perhaps this contributed the speed and fervour with which Sunday’s protesters turned their destructive powers onto the authorities:

Willy Lam was on RTHK radio mooting an interesting idea – in that the PRC gave the nod for HK activists to go to Diaoyu because the CCP does not trust the mainland activists.

Or, the HK activists are easier to put back in the box – plus it was clearly a cheap shot to give CY Leung some credibility, given that his response to the landing was about the most decisive thing any HK CE has ever done in such a quick time. Especially given that the HK CE has no foreign policy credentials to represent China.

Given Japan’s recent moves over Senkaku – the PRC needed to do something – but what?

Enter an eclectic mix of HK activists. Bear in mind, these people usually get pepper sprayed on the streets of HK for meeting outside the Beijing Liaison office – then suddenly they have the ability to give the authorities the slip and sail to Diaoyu unfettered?

Well the HK police’s story about boarding the boat but then giving up (as described in the NYT piece), it does sound very suspect. But I can’t understand the logic of what Willy’s saying – why would the PRC be more trusting of a group of pro-democracy & free-Tibet campaigners? Cos thats who these guys are: http://t.co/bHfFEf2a

Im actually inclined to believe the HK police might actually be telling the truth or at least some version of it. The real decision to allow them to go ahead, in my mind, it had to be made in the PRC’s Coastguard (PSB), which stopped them en route last time, and the other agencies that might have stepped in. It is understandable that none of them wanted to step in unilaterally; but there could well have been some order from higher-ups in Beijing that they be allowed to reach Diaoyu this time.

We don’t really have any way of knowing do we?

“Why would the PRC be more trusting of a group of pro-democracy & free-Tibet campaigners? ”

1. Because they are REALLY REALLY patriotic to the country. They think that the country and the party are two things most of the time. I think Yang wore “Free Tibet Now” just to shame Hu Jintao. 愛國不愛黨 (love the country but not the party) is the only sentence that can describe them. Now, even supporters of the League of Social Democrats are deeply disappointed because Tsang Kin-shing 曾健成 and Leung Kwok-hung 梁國雄 waved the Chinese flag, which we know the biggest star represents the party. Some people think that their pure patriotic hearts are exploited by the authority.

2. Now, on HK cyberspace, HK netizens always talk about how to get rid of China – real autonomy, independence or become a colony again… Even internet commentators have to resort to Chinese nationalism, like “when you go the West, you are still a Chinese in white people’s eyes. Don’t think that an Independence can make changes”. The reason why members from the League of Social Democrats are thought to be reliable because their goal is a democratic UNITED China. The keyword is UNITED. Separatism is the last thing they want.

3. The campaign is financially supported by the member of the national committee of CPPCC, Liu Mengxiong, a great supporter of CY Leung. There was a report that Liu Mengxiong had made a secret political deal with Tsang Kin-shing, who is a candidate in the Hong Kong Legislative Council Election on Sep 9.

4. Before HK Chief Executive “election” in March, Henry Tang’s people accused that CY Leung was a British trained spy and worked for MI5. His father was from British Weihaiwei and later recruited to Hong Kong police. (I personally don’t believe it.)

[…] excellent South Sea Conversations adds about the dangers of nationalism: The ICG’s Stephanie Kleine-Ahlbrandt recently commented that the leaders of China and Japan […]