China’s “blue territory” and the technosphere

Posted: April 19, 2017 Filed under: Academic debates, South China Sea | Tags: academia, blue territory, Chinese nationalism, Haus der Kulturen der Welt, HKW, maritime disputes, PRC maritime law enforcement, south china sea, technosphere, UNCLOS, UNCLOS and South China Sea 1 CommentI recently contributed an essay to Technosphere, a multimedia online magazine based out of Berlin’s Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW): China’s “Blue Territory” and the Technosphere in Maritime East Asia.

According to the magazine’s calculations, it’s a 648-second read.

It’s part of a set of presentations that comprise a dossier on the theme of land and sea. I can recommend checking out some of Technosphere’s other dossiers, especially those on creolized technologies and risk and resilience.

My contribution contains some of the arguments developed in my PhD thesis, which fortunately is now done and dusted. It’s titled “Chinese Popular Nationalism and PRC Foreign Policy in the South China Sea” — as always comments and criticisms are much appreciated, so if you feel like taking a look, you can download it by clicking on the title.

Comparison of Vietnam and China’s joint statements, 2011-2017

Posted: February 3, 2017 Filed under: China-Vietnam, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, South China Sea | Tags: arbitration, China-Vietnam, China-Vietnam joint statement, China-Vietnam relations, joint communique, Nguyen Phu Trong, nine dashed line, nine-dash line, Philippines vs China arbitration, Sino-Vietnamese relations, south china sea, South China Sea arbitration, UNCLOS, UNCLOS and South China Sea, Vietnam-China joint statement 2 Comments

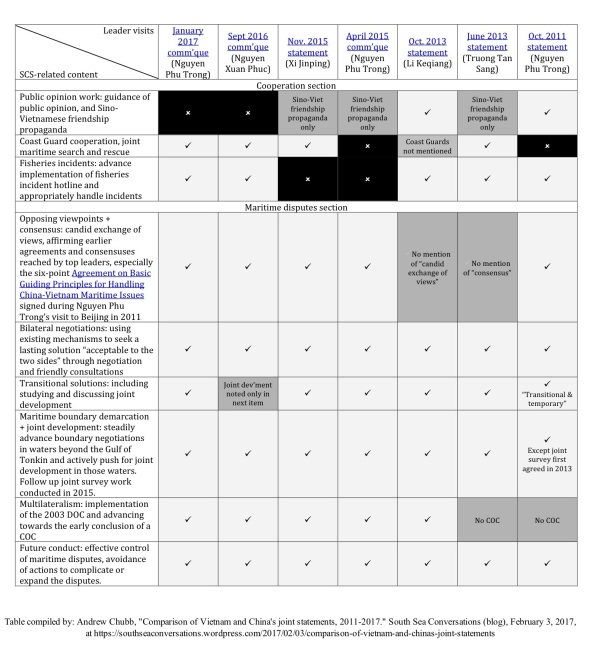

Comparison of Sino-Vietnamese joint statements since 2011 (click to enlarge). Links to sources: January 2017 communique (Nguyen Phu Trong visit to China); Sept 2016 communique (Nguyen Xuan Phuc visit to China); Nov. 2015 statement (Xi Jinping visit to Vietnam); April 2015 communique (Nguyen Phu Trong visit to China); Oct. 2013 statement (Li Keqiang visit to Vietnam); June 2013 statement (Truong Tan Sang visit to China); Oct. 2011 statement (Nguyen Phu Trong visit to China).

East Asia Forum has kindly published a piece from me on recent developments in Sino-Vietnamese relations. To supplement it, i’m posting here a table comparing the South China Sea-related elements of the last 7 joint statements between the two.

The comparative table was the basis for the article’s argument that General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong’s visit to Beijing last month did not involve any softening of Vietnam’s position on the issue.

According to a knowledgeable Vietnamese source, there are three types of Sino-Vietnamese bilateral joint statements issued after high-level meetings. In ascending order of importance these are:

- Joint press release (联合新闻公报, thông cáo báo chí)

- Joint communique (联合公报, thông cáo chung)

- Joint statement (联合声明, tuyên bố chung)

These documents are often not released in English, and some of the translations that have appeared have been incomplete or unreliable, so the table above compares the Chinese full text as published by state media (links are in the caption area above).

The table also includes an item, not discussed in the EAF article for space reasons, on cooperation in public opinion work. In the 2011 joint statement, the two sides pledged cooperation on “strengthening public opinion guidance and management” – which, in the context of several weeks of anti-China protests through the middle of that year, was tantamount to a Vietnamese undertaking to dampen anti-China sentiments.

Interestingly, however, there has been no analogous item in the recent joint documents — even after another, even more intense, wave of anti-China sentiments burst forth in 2014 during the HYSY-981 oil rig standoff. Its omission from subsequent documents might indicate an acceptance on China’s behalf of the strength Vietnamese nationalist sentiments that flow in its direction at times of heightened tensions. Perhaps also an acknowledgement that Hanoi is already doing what it can to promote Sino-Vietnamese friendship? Any other readings?

The EAF piece is reposted below. Based on some early feedback, i should have been clearer that in suggesting . . .

China may have pulled back from its pursuit of particular claims that have no basis in international law

. . . i do not mean the PRC has seen the light and is abandoning all claims deemed unlawful in the UNCLOS arbitration. Just that there are some unlawful aspects of China’s claims that it is no longer pushing, and this has removed some of the major drivers of Sino-Vietnamese tensions.

As always, further comments, arguments, additions and corrections are much appreciated.

[Updated] Defining the post-arbitration nine-dash line: more clarity and more complication

Posted: July 20, 2016 Filed under: Article summaries, China-Philippines, PLA & PLAN, South China Sea | Tags: arbitration, Central Party School, 王军敏, historic title, internal waters, Law of the Sea, nine dashed line, nine-dash line, Philippines vs China arbitration, PLA Daily, South China Sea arbitration, straight baselines, UNCLOS and South China Sea, Wang Junmin 8 Comments

The Central Party School’s article, headlined, “China does not accept the jurisprudential legitimacy of the SCS arbitral tribunal’s decision,” PLA Daily, July 18, p.6

One week on from the UNCLOS arbitration ruling on the South China Sea, the PRC’s response continues to somehow both clarify and complicate the issue at the same time. The latest episode in the unfolding mystery of the nine-dash line seems to diminish the line’s linkage with oil and gas claims designated unlawful by the Tribunal, while ramping up its associations with “historic title” over large sweeps of archipelagic waters [but seemingly not the entire Spratly archipelago – see update at the bottom].

On Monday an article published on p.6 of the PLA’s official newspaper offered a clear and detailed post-ruling definition of the nine-dash line from authors at the Central Party School. One of its main purposes was to refute the Tribunal’s inferred reading of the nine-dash line as a blanket claim to historic rights within the area it encloses. (Grateful HTs to Bill Bishop for digging it up and Bonnie Glaser for drawing attention to its significance.)

The article offers a more complex clarification of the line’s meaning than my optimistic reading of last week’s PRC Government Statement: whereas i read the Statement as implicitly separating the nine-dash line from China’s maritime rights claims, this article spells out at least some explicit links between the two.

On the other hand, it offers little or no support to the expansionist reading of the line that has underpinned many provocative PRC actions in recent years. In particular, the CPS scholars’ definition does not appear to support a claim to oil and gas resources out to the edge of the nine-dash line. This was a key element of the implied reading of the nine-dash line that the Tribunal struck down as unlawful. It’s a position that the PRC has backed up with coercion against other claimants’ energy survey ships in the past, and it’s also the basis for the notion, widespread in PRC domestic discourse, that rival claimants, especially Vietnam and Malaysia, are “plundering” China’s resources.

The writing of this article is attributed to CPS Postgraduate Studies Institute Deputy Dean Wang Junmin 王军敏, but the newspaper byline attributes it collectively to the CPS Center for Research on the Theoretical System of Socialism With Chinese Characteristics. It is, as such, not a government statement, but it’s very detailed, takes into account the Tribunal ruling, and could end up being close to the interpretation the PRC goes forward with in the wake of the ruling.

This interpretation can be summarized as follows. The nine-dash line is not a blanket claim to historic rights over all waters within, but rather to three distinct sets of rights across different geographical areas:

- Sovereignty over the islands within the line (the original meaning of the line when the KMT government published it in 1948)

- “Historic title” (历史性所有权) to waters enclosed by straight baselines drawn around island groups within the line (definitely including the Paracels, for which the baselines have already been announced, but not necessarily for the whole Spratly group)

- Non-exclusive fishing rights in others’ EEZs where (a) they overlap with the line and (b) Chinese fishers traditionally fished under high-seas freedoms

The article begins by arguing the UNCLOS does not constitute the entirety of international maritime law, and that customary international law continues to apply on matters where rules are not provided for in UNCLOS. In particular, the authors argue,

“The UNCLOS did not provide rules for the issue of territorial sea baselines for continental countries’ archipelagos; nor did it provide rules for historic rights, although it affirmed their status in international law.”

The author(s) state that the Philippines “distorted” the nine-dash line by (a) presenting it to the arbitral tribunal as representing a Chinese claim to sovereign rights and administration over all of the waters and seabed within; and (b) by arguing that the PRC claims “historic rights” (历史性权利) within the line, when in fact the PRC claims “historic title” (历史性所有权) over areas within the line, putting the case outside the Tribunal’s jurisdiction.

This line of argument appeared, fleetingly, in China’s 2014 Position Paper, which noted that disputes concerning “historic bays or titles” were exempt from compulsory dispute resolution under Article 298. According to the author(s), China has “historic title” to internal waters within archipelagic straight baselines.

So the authors say the Philippines “slandered” China’s nine-dash line by providing a distorted reading of its meaning to the Tribunal. Here’s how they explain its true meaning:

First, looking at China’s practical exercise of state power, China has never claimed all the waters within the line as its territorial sea or internal waters, exercising state sovereignty there. In fact, the 1958 Territorial Sea Declaration, at the same time as proclaiming the applicability of the straight baseline system and setting the breadth of China’s territorial seas at 12nm, implicitly noted that international waters [exist] between the Chinese mainland and coastal islands, and Taiwan and surrounding islands, Penghu, Pratas, Paracels, Zhongsha, Spratlys and other islands belonging to China [ZH]. In 1996 the Declaration of Territorial Sea Baselines announced the territorial sea basepoints and baselines for the Paracel Islands, thereby implying that within the ‘nine-dash line’ China would, in accordance with the UNCLOS, take the Paracels as an integrated whole entitled to territorial seas, contiguous zone, EEZ and continental shelf. Likewise, China’s 2011 note to the UN Secretary General claimed that the Spratlys also enjoy territorial seas, EEZ and continental shelf. This implies: China has never claimed all the waters within the ‘nine-dash line’ as China’s historic waters or that it enjoys historic rights .

Second, the Philippines used the Chinese expression ‘historic rights’ (历史性权利) to argue China had not claimed ‘historic title’ (历史性所有权). As everyone knows, historic rights in international law refers to the rights enjoyed continuously by a state in certain waters since ancient times. Historic rights include historic title and non-exclusive historic rights. Waters subject to historic title are called ‘historic waters’ (历史性水域), these are part of a coastal state’s internal waters or territorial seas, and mainly include historic bays. other coastal waters adjacent to the coast, and the waters within archipelagos. Non-exclusive historic rights are divided into historic rights of passage and historic fishing rights. The former refers to innocent passage through internal waters, specifically all countries’ rights of innocent passage through areas not originally regarded as internal waters, but which became enclosed as such through the coastal state’s application of straight baselines.[ZH] The latter refers to non-exclusive rights to fish in areas that were previously fished in accordance with high seas freedoms but which have now become a coastal state’s EEZ [or] archipelagic waters.[ZH] The mere use of ‘historic rights’ in the PRC EEZ and Continental Shelf Law, by MFA spokespersons, and by Chinese scholars, does not imply China does not claim ‘historic title’. In fact, our country has historic title and historic fishing rights in different areas within the nine-dash line.

Third, China’s ‘nine-dash line’ rights claims mainly comprise: 1. China has territorial sovereignty over islands, reefs, cays and shoals within the line; 2. China has historic title to waters within archipelagos or island groups that are at relatively close distance and that can be viewed as an integrated whole, these areas are China’s historic waters, they are our country’s internal waters,[ZH] and China has the right to draw straight baselines around the outermost points of these waters and claim state administrative zones such as territorial seas, EEZs and continental shelves etc. in accordance with the UNCLOS. 3. When waters within the ‘nine-dash line’ become [part of] another country’s EEZ or an archipelagic state’s waters, China has the right to claim historic fishing rights or traditional fishing rights in the overlapping areas.

The many references to non-exclusive fishing rights contrast sharply with the complete absence of any mention of claims to oil and gas rights. As noted, it was precisely that (implied) claim that led to the line being designated unlawful. The 2012 CNOOC oil blocks, especially, convinced the Tribunal that China was acting in accordance with this reading of the line (see especially the Award paragraphs 208-214). But under the above definition, the nine-dash line seems to have no significance at all to the geographic scope of China’s energy rights claims.

The other striking thing about this definition is the heavy focus on the issue of historic title over internal waters enclosed within straight baselines around island groups — an issue addressed in an excellent article by Yanmei Xie over the weekend. There is plenty of reason to think that straight baselines might be about to enclose the Spratlys, a move that would significantly harden the PRC’s position.

But there might be yet another strange twist here. Looking again at the third paragraph above, the Party School authors define China’s claim of historic title to internal waters as existing in “archipelagos or island groups that are at a relatively close distance and that can be viewed as an integrated whole (my emphasis).” Which kinda seems to suggest the historic title aspect might be referring to the Paracels but not the Spratlys.

I’ve heard the “can be viewed as an integrated whole” argument for archipelagic straight baselines in the South China Sea numerous times from PRC sources, but i’ve never come across the “at a relatively close distance” criterion before. Why else might they have included this?

Here’s the answer (update 21/7):

Dylan Jones points out that the relatively close distance criteria refers to the distances between the islands, and a careful re-reading of the article confirms this. Here’s the Central Party School authors’ detailed explanation in translation:

“Most international legal experts consider state practice is forming, or has already established, international legal norms regarding continental states’ offshore archipelagos: the straight baseline system’s applicability to continental states’ offshore archipelagos is restricted to those archipelagos that can be seen as an integrated whole, with relatively small distances between the islands, and intimate connections between the waters and the mainland [. . . ]

“The most likely and most appropriate method for China’s territorial sea baselines in the Spratly Islands is to imitate the method used in the Diaoyu Islands, for example, taking the main islands and reefs such as Itu Aba, Pagasa, West York, Spratly and Mischief as the centre, and linking together the surrounding reefs to establish baselines [. . .]”

“Looking at historic rights, China has historic title to waters between the relatively close, intimately connected islands that qualitatively comprise a unified whole, these waters are historic waters, China’s internal waters . . . China has the right to take those groups of islands within the Spratlys that are relatively close to each other as a single entity to establish territorial sea baselines,[ZH] and China’s Spratly Islands in the SCS have maritime administrative zones such as territorial seas, EEZ and continental shelf.”

So the author(s) do in fact believe a “historic title” claim over “internal waters” enclosed by straight baselines exists in the Spratlys — but rather than covering the entire archipelago, as per the Paracels baselines in 1996, it would only cover those parts within the archipelago that are close together. Here’s the Diaoyu example they refer to:

Diaoyu Islands straight baselines submitted to the UN in 2012

The authors repeat this “within the Spratlys” + “close together” + “intimately connected” recipe for Spratly straight baselines (and thus the scope of internal waters subject to historic title) no less than 6 times, so it’s fair to conclude this was a point they were keen to get across. That would be a tough sell domestically given that it would probably exclude James Shoal, that shallow patch of ocean considered by many (probably most) Chinese people to be the southernmost point of the nation’s sacred territory. This would be one reason to think the party might not make a Spratly baseline declaration in the near future after all.

Another rambling post…i really ought to shut up and let things run their course. But the riddle of the nine-dash line continues to string me along rather compulsively. If any readers have made it this far then at least i mustn’t be the only one.

The “next level smearing” of Chinese patriotism: a view from the Communist Youth League

Posted: July 19, 2016 Filed under: Academic debates, Article summaries, China-Philippines, China-US, Mouthpieces, State media, Weibo | Tags: angry youth, arbitration, audience costs, boycotts, Chinese nationalism, Communist Youth League, 表情包, memes, nationalist demonstrations, nationalist mobilization, online nationalism, Philippines vs China arbitration, Sina weibo, South China Sea arbitration, UNCLOS and South China Sea, Weibo 6 Comments

“There’s the door”: one of many Communist Youth League-approved “memes” on the South China Sea issue

The first weekend after the July 12 Philippines vs China arbitration ruling — the “7.12 Incident” — has passed without reports of major anti-foreign protests.

There were, however, scattered cases of nationalist mobilization. There was at least one case of picketing outside a KFC in Hebei province (video), some smashing of iPhones (footage of which was often shared via iPhones), and a bunch of online dried mango retailers claiming to have switched their suppliers away from the Philippines.

Together with the various patriotic outpourings online, this was probably the largest set of collective actions by Chinese citizens on the South China Sea issue yet seen in China — bigger than Scarborough Shoal in 2012, or the peak of tensions in 2011, though still probably smaller and less intense than the demonstrations that would likely have occurred during the 2001 Sino-American EP-3 incident, had authorities had not prevented them.

While the Global Times hailed the “new wave of patriotism,” it was clear that, like in 2001, the party-state did not want real-world demonstrations. Municipal and university authorities were reportedly instructed to stay vigilantly on guard against potential mass gatherings. Nor, it seems, was online warmongering particularly desirable from the party’s perspective, with jingoistic Weibos encountering censorship.

An article published on the Communist Youth League’s Weibo illuminates some of the reasoning behind this desire to keep the patriotic outbursts relatively mild. It argues that much of the extreme nationalist outbursts are in fact “next-level smearing” (高级黑, referred to below as gaojihei) of China’s good patriots by anti-party elements posing as extreme nationalists.

Just how much of China’s ultra-nationalist output this actually accounts for is a wide open question. But the article offers evidence that it does explain at least some of the most visible and intense cases of what the outside world commonly understands as Chinese nationalism. In this way, it’s another illustration of how much more lurks behind shows of apparently anti-foreign mobilization besides simple “nationalist” ideology.

The examples cited suggest at least 4 distinct kinds of anti-regime motivation for extreme nationalist speech and actions:

- Critiquing the party’s ideological policies through parody;

- Giving patriotism negative associations;

- Fomenting domestic chaos that would destabilize party rule;

- Pushing for a war that would likely be disastrous for the party.

The article is written by one of the Communist Youth League’s most energetic proponents of pro-party “positive energy” in both China and Australia. Besides being on the committee of the All-China Youth Federation, Lei Xiying is a PhD student at Australian National University, whose previous projects include the “take a selfie with the flag,” setting up an Association for PhD Students and Outstanding Youth Scholars, and heavy promotion of last year’s military parade. He’s a prolific political commentator in the PRC state media, as well as in the Chinese-language media in Australia.

The author is, in short, a very worthy recipient of his Positive Energy Youth award bestowed on him by the Cyberspace Administration of China for being an “outstanding youth representative of online ideological construction.” As such, the article is illustrative of some of the issues facing the state’s leadership of popular nationalism on contentious foreign policy issues in the internet era, which i’ll return to briefly at the end.

~

Life’s-a-game memes and the hijacking of youth patriotism by “crazy uncles”

游戏人生的表情包与当代青年被“怪蜀黍”绑架的“爱国”

Communist Youth League Weibo, July 16, 2016

Lei Xiying

“A gift for American President Putin”

This afternoon a post-1995 netizen sent me a “patriotic” photograph that he found confusing.

At a glance, with the slogan “violators of my China, however distant, must be punished” it’s a hot-blooded emotional “patriot.” But look a bit closer . . . Excuse me? [The calligraphic banner] is “a gift for US President Putin” . . . look again, a bald, bespectacled, half-naked, very inelegant “crazy uncle” with bad posture hits your eye . . .

“Bro, his patriotic expression is weird, how could he say the American President is Putin…”

I replied to this post-95’s doubts in three decisive words: next! level! smear! (高!级!黑!)

Is this surprising? Actually no, it’s commonplace. Whenever big things happen in China, whenever the whole population’s patriotic sentiments rise, these kinds of gaojihei are sprayed out everywhere.

For example, the author says, during the Diaoyu crisis, a person who had once burned the 5-star red flag suddenly became a patriotic Diaoyu defender, inciting the masses to take to the streets. Other suspect “patriots” had bragged about using the occasion to help themselves to a free meal or Rolex watch. “As for those among the peaceful patriotic marchers who urged violence and looting, their shouting of patriotic slogans was the loudest, but what was their objective?”

In one common gaojihei, Lei notes, netizens purported to blame actress Zhao Wei, who has again been the target of nationalist criticism of late, for masterminding the South China Sea arbitration decision, the Turkish coup attempt, and the Nice terror attack in order to divert attention from her sins.

Satirical posts blaming recent events, including the South China Sea arbitration, on Zhao Wei

Lei makes an important distinction between those who initiate extreme nationalist actions and those who join in later:

The initiators of this type of information are generally troublemakers, while those who forward it on are overwhelmingly ordinary netizens with naive patriotic sentiments — their heart is good, but due to their unfamiliarity with the internet’s complex public opinion environment, they are used by people with a purpose.

Besides these, some groups who are normally very dissatisfied with the state, the current system and the present state of affairs, suddenly become interested in patriotism, and urge everyone to take to the streets, and take to the battlefield.

The author then provides several examples of such suspects.

Another concern is the attempts to link party-sactioned patriotism with the sickening violence seen in the anti-Japan demonstrations over the Diaoyu Islands in 2012.

Some people take the opportunity to smear and exaggerate the behaviour of “extremist elements,” and use this to “represent” and “denounce” the rational behaviour of the overwhelming majority of patriotic youth, enacting maximum distortion on patriotism.

Have we taken to the streets and smashed things? Committed violence? We are just playing with memes (表情包), OK?

Weibo post on July 14 recalling protester Cai Yang’s horrific hammer attack on Toyota driver Li Jianli during the 2012 anti-Japan protests in Xi’an

The author then takes the opportunity to address some other criticisms of South China Sea patriotism. A comment observing two main types of nationalists, “very smart swindlers” and “very emotional idiots,” comes remarkably close to Lei’s own analysis of the initiators and followers noted above. Not surprisingly, his rebuttal does not acknowledge any such parallel:

Please do not force these meaningless labels on us, OK? If you must label us, we are the ‘party of memes’ (表情包党), OK?

In response to a middle-aged Weibo user’s observation that outbursts of patriotism tend to involve the denouncing of race-traitors:

We love the country but we do not arrest traitors, that was your generation’s hobby, our hobby is memes, OK?

“What you’re doing is moral hijacking”: one of the Communist Youth League patriotic meme gang’s responses to the critics

In the words of noted scholar Liu Yang 刘仰: “If you trace the patriotic demonstrations over the past few years, you find that every time patriotic enthusiasm is ignited, a succession of acts of sabotage follow. Strong voices immediately appear afterwards, saying patriots are ‘angry youth,’ patriots are criminals, patriots are extremist terrorists, patriots are ignorant brain-dead! . . . Time after time patriotic enthusiasm has ended in farce. This may be the behind-the-scenes manipulators’ objective: [keep this pattern repeating] until one day when China really needs the power of patriotism no one will appear, like the villagers in the Boy Who Cried Wolf or King You’s generals after he played with the fire beacons (‘烽火戏诸侯’故事里的勤王之师).”

Thankfully, according to the author, the plot was thwarted thanks to the Communist Youth League sending out articles such as his own, discouraging any boycotts of any country’s products, and designating memes as the “patriotic form” of choice for today’s youth.

“I’m not giving you a single fish from my South China Sea”

In conclusion Lei notes that critics of patriotism had different motivations corresponding to their generations. In contrast to the post-1970 and post-1980 generations (who presumably act on the basis of their westernised values), post-1950 and post-1960 critics of contemporary youth patriotism are often driven by their disillusionment with “the current system, road, and theory.” The article finishes with a rousing affirmation of the current generation:

Our understanding of history, of China, and of the world is inevitably more complete, more objective, more rational than that ‘historically burdened’ generation

. . .

this is why, after the 7.12 arbitration incident, we did not take to streets, scream protests, or even smash things up as some people had hoped . . . on the contrary we initiated a form of ‘mocking and scolding’ (嬉笑怒骂) unique to this generation.

“Your ignorance pains me”

~

Not sure if the summary above hangs together at all — the article itself is similarly disjointed — but it does raise a couple of issues facing the state’s leadership of popular nationalism on contentious foreign policy issues in the internet era.

First, as the Liu Yang quote suggests, the CCP state’s ability to tap into the power of popular nationalist mobilizations is significantly compromised by the moderate backlash their extreme elements generate. This point, borne out in Chris Cairns and Allen Carlson’s recent study of the 2012 wave of nationalism, has been recognized by other smart minds within the propaganda system. In a research interview in 2013, a state media employee familiar with audience costs theory observed that any international leverage China may gain from allowing domestic protests is greatly diminished when violence ensues. Not only does protest violence require suppression, thereby foregrounding the state’s ability to control nationalist outrage. It also brings forth strong anti-nationalist voices from across society, suggesting popular support for defiance of nationalist demands for escalatory foreign policy choices.

Second, perhaps reflecting the need to protect trade ties in a time of economic uncertainty, the CYL was clearly keen to specifically discourage boycotts among the youth, and substitute them with online “memes” (表情包). For the party-state to adopt these particular forms of internet-era youth expression as a vehicle for its propaganda makes perfect sense. But as a substitute for real political action it’s so openly inconsequential (and, due to the need for political correctness, humourless) that i wonder how this could possibly satisfy any genuine nationalist anger about the South China Sea issue — let alone the kind of general dissatisfaction with life that underpins at least part of it. This might be why some of the approved “memes” contained nods in the direction of slightly more violent Cultural Revolution-esque imagery (e.g. the one below).

What else is going on here? What am i missing about this “meme” strategy? As always, thoughts, suggestions, corrections etc. most welcome.

“You, a banana seller, dare to scramble with daddy for the South China Sea!”

Did China just clarify the nine-dash line?

Posted: July 12, 2016 Filed under: South China Sea | Tags: historic rights, nine dashed line, nine-dash line, Philippines vs China arbitration, South China Sea arbitration, UNCLOS, UNCLOS and South China Sea 5 Comments

Locations of China’s 2011-2012 coercive operations against foreign energy surveys. As far as i’m aware, no similar incidents have been reported in these areas since that time. Also shown in green is the maximum EEZ area the PRC might have claimed in the SCS under UNCLOS before the arbitral tribunal ruled that there are no proper islands in the Spratly archipelago. This reduced China’s maximum legal claim under UNCLOS to the sprinkling of 24 nautical mile-wide circles roughly indicated on the map. (Compiled using Google Earth, incident coordinates found in official materials, and Greg Poling’s CSIS report.)

I’m going to make this very quick because i should get back to reading a 501-page piece-by-piece dismantling of maybe 95% of China’s maritime claim south of the Paracels.

Unless i’m mistaken (again), i think the official Statement of the Government of the People’s Republic of China in response to the arbitration result might just have made an important and long-awaited clarification of the meaning of the nine-dash line.

The status of a PRC Government Statement is about as high as a statement’s status can get in the the PRC system. This one contains five numbered points, each explaining a different aspect of the PRC’s position.

- China’s historical claim to territorial sovereignty and “relevant rights and interests” over islands in the SCS

- The PRC government’s actions to uphold said sovereign rights and interests since 1949

- Four elements of the PRC’s rights and interests in the SCS:

- Sovereignty over SCS islands,

- Internal waters, territorial seas & contiguous zones based on SCS islands

- EEZ & Continental Shelf based on SCS islands

- Historic rights

- China’s opposition to other countries’ occupation of some of the Spratly archipelago

- China’s commitment to freedom of navigation for international shipping

I’m pretty sure this is the most comprehensive encapsulation of China’s claims in the South China Sea ever made. None of the elements are new, but i don’t think they’ve all appeared side-by-side in one document before. The claim to “historic rights”, for example, is included in the PRC’s 1998 EEZ & Continental Shelf law, but that document doesn’t refer to the nine-dash line. A diplomatic note to the UN in 2009 included the nine-dash line map for the first time officially, but didn’t mention historic rights. And another 2011 note to the UN specified that the Spratlys were entitled to EEZ and Continental Shelf, but didn’t include the nine-dash line map or “historic rights”.

Of particular note is the Statement’s treatment of the nine-dash line. The first paragraph of point 1 begins by referring to its sovereignty over the territories of the Spratlys, Paracels, etc., states that China’s activities there date back 2,000 years, and then concludes that this established “territorial sovereignty and relevant rights and interests.” What’s especially interesting is that an explanation of the nine-dash line is presented separately in a second paragraph (also under point 1) that reads:

“Following the end of the Second World War, China recovered and resumed the exercise of sovereignty over Nanhai Zhudao which had been illegally occupied by Japan during its war of aggression against China. To strengthen the administration over Nanhai Zhudao, the Chinese government in 1947 reviewed and updated the geographical names of Nanhai Zhudao, compiled Nan Hai Zhu Dao Di Li Zhi Lue (A Brief Account of the Geography of the South China Sea Islands), and drew Nan Hai Zhu Dao Wei Zhi Tu (Location Map of the South China Sea Islands) on which the dotted line is marked. This map was officially published and made known to the world by the Chinese government in February 1948.”

The nine-dash line, according to this authoritative statement, was created to “to strengthen the administration over” the Chinese-claimed islands of the South China Sea. No mention of “historic rights.”

The omission of a link between the nine-dash line and China’s “historic rights” wouldn’t, on its own, mean much, if they weren’t mentioned elsewhere in the statement. But they are: they are on the list of 4 elements that comprise the PRC’s maritime claims, where they are once again listed separately from the territorial claims represented by the nine-dash line.

This seems to imply very strongly that the nine-dash denotes the extent of the area within which China claims sovereignty over islands, and does not demarcate the extent of the area within which China maintains a claim to “historic rights,” which had been one of the most likely readings.

The separate treatment of the nine-dash line strongly implies that the nine-dash line does not depict the geographical extent of the PRC maritime rights claim.

If this implication was intended, it should be apparent in China’s behaviour. One sign in favour of this reading is that the PRC’s “cable-cutting” operations against Vietnamese survey ships around the edge of the nine-dash line area in 2011 and 2012 seem to have ceased since that time (see above map).

Going forward, if this is correct, we might also expect to see a winding back of China’s opposition to other countries’ activities near the edges of the nine-dash line, such as Vietnam’s oil and gas projects in the Nam Con Son Basin. And the path of the PRC Coast Guard’s “regular rights defense patrols” should no longer hug the nine-dash line. Where fishing in the “traditional fishing grounds” off the Natuna Islands (mostly outside the nine-dash line) might fit in, i’ve no idea.

And with the nine-dash line appearing decoupled from “historic rights” in a Statement of the PRC Government, this should mandate the same treatment to be repeated in future statements by lower-level authorities like individual leaders, the MFA and its spokespersons.

Time to get back to work, long and fascinating night ahead….please share any thoughts and corrections. I can only hope my hasty read of this present statement might turn out a little closer to the mark than my prediction of the arbitration outcome.

South China Sea arbitration: don’t count on a decisive Philippines win

Posted: July 10, 2016 Filed under: China-Philippines, State media, Xinhua | Tags: AIIA, arbitration, Australian Institute of International Affairs, China-Philippines relations, external propaganda, Law of the Sea, Philippines vs China arbitration, Philippines vs China case, south china sea, South China Sea arbitration, UNCLOS, UNCLOS and South China Sea, 强词夺理 1 Comment

Thomas A. Mensah, Presiding Arbitrator of the Philippines vs China arbitral tribunal. Among Judge Mensah’s many qualifications, he was the inaugural President of the ITLOS, on which he served from 1996 to 2005. Contrary to PRC propaganda claiming the arbitral tribunal is “presided over by a former Japanese diplomat” Judge Mensah is from Ghana.

Here’s a bit of speculation ahead of the UNCLOS arbitration decision on Tuesday, written for the Australian Institute of International Affairs’s website.

My argument is that, however shrill and legally unconvincing the PRC’s propaganda campaign may seem, it will force the tribunal to take politics into account to an even greater extent than it would have otherwise — so expect some significant concessions to China. As Bill Bishop points out, the CCP has a long tradition of overcoming deficiencies of reason via sheer force of rhetoric (强词夺理). Of course, i could be proved wrong in short order; if so, things may get very interesting for the PRC’s relationship with the UNCLOS.

I’ve also added in the page numbers of the article’s references to the tribunal’s Award on Jurisdiction. Obviously i’m not a lawyer and it’s a case where the fine-grain details are crucial, so i’d especially appreciate any corrections.

~

South China Sea arbitration: don’t count on a decisive Philippines win

AIIA Australian Outlook

July 7, 2016

By Andrew Chubb

On 12 July, an international arbitral tribunal will hand down its findings in a landmark case brought by the Philippines against China over the South China Sea issue. The decision will have far-reaching implications, not only for this contentious maritime dispute but also for international law and politics in East Asia.

United States officials have expressed concern that the decision may exacerbate tensions in the region if China responds to an adverse finding with new assertive moves in the disputed area. However, contrary to the expectations of many observers, a total victory for the Philippines is unlikely. At least some key findings will probably favour China due in part to the political interest of the tribunal in protecting the status and relevance of the law of the sea in international politics.

The case has been particularly contentious due to China’s allegation that the Philippines is “abusing” the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) processes. China’s subsequent refusal to take part in the proceedings, relentless propaganda campaign aimed at delegitimising the tribunal among domestic and international audiences, and its frenetic efforts to enlist statements of support from foreign governments, have created a backdrop that means the tribunal is unlikely to decide the case on legal merits alone.

Even if the merits of the Philippines’ claims are strong, the arbitrators will be keen to avoid appearing to make a one-sided ruling. Instead, they will seek to make at least some concessions to China in order to neutralise Beijing’s political attacks on the tribunal’s authority, minimise the political fallout, and forestall the possibility of a Chinese withdrawal from UNCLOS. The latter scenario, while highly unlikely, would be a major disaster for the cause of international law, so it is likely to be among their considerations as legal professionals.

.

The current state of play

The Philippines has asked the arbitral panel to rule on 15 specific questions concerning the South China Sea with the aim of clarifying the limits of the sea areas that China can legally claim under UNCLOS. The Philippines’ contentions can be summarised as:

- China’s claims to “historic rights” within the nine-dash line are invalid under the Convention (submissions 1 & 2)

- Scarborough Shoal is not an island, and therefore generates no entitlement to maritime rights beyond 12 nautical miles (nm), such as an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) or Continental Shelf (submission 3)

- China’s outposts in the disputed Spratly archipelago are also not islands, and therefore also generate no EEZ or Continental Shelf entitlement (submissions 4, 5, 6 & 7)

- China has conducted maritime law enforcement and economic exploitation activities in areas where it does not have any lawful claim, thereby violating the Philippines’ lawful rights under the Convention, while also violating the Convention’s safety requirements (submissions 8, 9, 10, 13 & 14)

- China’s massive island-building projects breach the Convention’s rules on artificial islands, constitute unlawful appropriation of maritime spaces, and violate the Convention’s obligations not to damage the marine environment – as do its fishing, coral and clam harvesting activities at Scarborough Shoal and in the Spratly Islands (submissions 11 & 12)

The Philippines is also asking the tribunal to order China to drop any unlawful claims and desist from any unlawful activities (submission 15).

In response, China argues that these matters are “in essence” issues of territorial sovereignty, which UNCLOS was not intended to govern, and maritime boundary demarcation on which China has invoked its right to reject compulsory dispute resolution. Beijing also argues the Philippines is legally bound by its previous “commitments” to settle its disputes with China through bilateral negotiations.

However, in October 2015, the tribunal issued its preliminary award and found that it is competent to rule on at least seven of the Philippines’ 15 claims against China. In an official statement, China expressed anger at the ruling, this time accusing both the Philippines and the arbitrators themselves of having “abused the relevant procedures”. Notably, however, it avoided any suggestion that it was rejecting the UNCLOS itself.

.

Political considerations

Numerous analysts, including many in Manila both inside and outside government, expect that when the arbitral tribunal hands down its final award, the ruling will find in favour of the Philippines.

But as Phillipines legal academic Jay Batongbacal has noted, the tribunal had a strong incentive to accept jurisdiction over the case because doing otherwise would have been tantamount to an admission that UNCLOS is irrelevant in one of the world’s most important waterways, and one of its most dangerous maritime hotspots.

However, the same considerations make a total victory for the Philippines unlikely. Not only would this outcome draw even more furious political attacks on the tribunal’s authority from China, a decision seen as one-sided would increase the rhetorical bite of Beijing’s international propaganda.

The Award on Jurisdiction issued last October foreshadowed findings favourable to China on some key issues. For example, it noted that if China’s island-building and law enforcement actions are found to be “military in nature” then it may be unable to rule on their legality as these are excluded from the Convention’s dispute resolution procedures (p.140).

Perhaps even more importantly, the Award (pp.62-63) also flagged the possibility of the tribunal providing an implied reading of the nine-dash line’s meaning for China: development that could effectively legalise the PRC’s infamously unclear and expansive claim.

.

What to expect

The case’s greatest significance may lie in providing the first legal precedent defining specific criteria for what constitutes an “island” (entitled to an Exclusive Economic Zone and Continental Shelf under UNCLOS), as opposed to a “rock” (which is only entitled to 12 nautical miles of territorial sea).

Previous international legal rulings have deliberately avoided this question, but the Philippines’ submission has put the issue front and centre. The Award explicitly noted that “the Philippines has in fact presented a dispute concerning the status of every maritime feature claimed by China” in the disputed area (p.72). This suggests the tribunal may make the long-awaited definition. This would also accord with the arbitrators’ imperative to maximise UNCLOS’ relevance in international politics as it would help clarify the status of other disputed maritime rights claims in Asia and beyond, notably Japan’s claim to a 200nm EEZ around Okinotorishima.

It is no certainty that this will happen. It remains possible that the tribunal would simply rule that there may exist one or more islands within 200nm of the relevant areas: a conclusion that would be sufficient to prevent consideration of the Philippines’ claims against China in those areas.

Although the case is too complex to predict specific findings with certainty, the Philippines’ best hopes probably lie in obtaining an explicit rejection of China’s claims to “historic rights” and an affirmation that Scarborough Shoal—but not the much larger Spratly archipelago—is a rock and not an island, meaning the surrounding waters outside 12nm cannot be subject to any legitimate Chinese claim.

US officials worry that the ruling may exacerbate tensions in the region if China responds to an adverse finding with more assertive moves. Reclamation activities at Scarborough Shoal and the declaration of an Air Defense Identification Zone in the South China Sea have been touted as possible responses.

Despite China’s decision to ignore the tribunal’s verdict, it has major stakes in UNCLOS’ ongoing viability. These include deep seabed mining concessions in international waters and its outer continental shelf claim in the East China Sea. UNCLOS is also central to China’s argument that US naval surveillance activities off its coast are illegal.

This leaves Beijing in the awkward position of trying to cast itself as a defender of UNCLOS while ceaselessly attacking an arbitration process constituted directly under its auspices. The continuation or even intensification of China’s political campaign threatens the global authority of UNCLOS as it seeks to divide signatory states into opposing camps. I may be proved wrong on Tuesday but I suspect the SCS tribunal’s arbitrators will be only too aware of this as they prepare their ruling.