Comparison of Vietnam and China’s joint statements, 2011-2017

Posted: February 3, 2017 Filed under: China-Vietnam, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, South China Sea | Tags: arbitration, China-Vietnam, China-Vietnam joint statement, China-Vietnam relations, joint communique, Nguyen Phu Trong, nine dashed line, nine-dash line, Philippines vs China arbitration, Sino-Vietnamese relations, south china sea, South China Sea arbitration, UNCLOS, UNCLOS and South China Sea, Vietnam-China joint statement 2 Comments

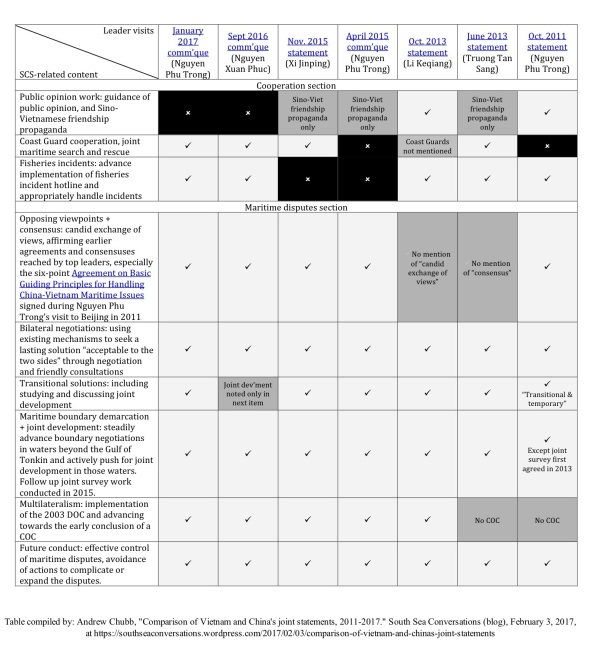

Comparison of Sino-Vietnamese joint statements since 2011 (click to enlarge). Links to sources: January 2017 communique (Nguyen Phu Trong visit to China); Sept 2016 communique (Nguyen Xuan Phuc visit to China); Nov. 2015 statement (Xi Jinping visit to Vietnam); April 2015 communique (Nguyen Phu Trong visit to China); Oct. 2013 statement (Li Keqiang visit to Vietnam); June 2013 statement (Truong Tan Sang visit to China); Oct. 2011 statement (Nguyen Phu Trong visit to China).

East Asia Forum has kindly published a piece from me on recent developments in Sino-Vietnamese relations. To supplement it, i’m posting here a table comparing the South China Sea-related elements of the last 7 joint statements between the two.

The comparative table was the basis for the article’s argument that General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong’s visit to Beijing last month did not involve any softening of Vietnam’s position on the issue.

According to a knowledgeable Vietnamese source, there are three types of Sino-Vietnamese bilateral joint statements issued after high-level meetings. In ascending order of importance these are:

- Joint press release (联合新闻公报, thông cáo báo chí)

- Joint communique (联合公报, thông cáo chung)

- Joint statement (联合声明, tuyên bố chung)

These documents are often not released in English, and some of the translations that have appeared have been incomplete or unreliable, so the table above compares the Chinese full text as published by state media (links are in the caption area above).

The table also includes an item, not discussed in the EAF article for space reasons, on cooperation in public opinion work. In the 2011 joint statement, the two sides pledged cooperation on “strengthening public opinion guidance and management” – which, in the context of several weeks of anti-China protests through the middle of that year, was tantamount to a Vietnamese undertaking to dampen anti-China sentiments.

Interestingly, however, there has been no analogous item in the recent joint documents — even after another, even more intense, wave of anti-China sentiments burst forth in 2014 during the HYSY-981 oil rig standoff. Its omission from subsequent documents might indicate an acceptance on China’s behalf of the strength Vietnamese nationalist sentiments that flow in its direction at times of heightened tensions. Perhaps also an acknowledgement that Hanoi is already doing what it can to promote Sino-Vietnamese friendship? Any other readings?

The EAF piece is reposted below. Based on some early feedback, i should have been clearer that in suggesting . . .

China may have pulled back from its pursuit of particular claims that have no basis in international law

. . . i do not mean the PRC has seen the light and is abandoning all claims deemed unlawful in the UNCLOS arbitration. Just that there are some unlawful aspects of China’s claims that it is no longer pushing, and this has removed some of the major drivers of Sino-Vietnamese tensions.

As always, further comments, arguments, additions and corrections are much appreciated.

[Updated] Defining the post-arbitration nine-dash line: more clarity and more complication

Posted: July 20, 2016 Filed under: Article summaries, China-Philippines, PLA & PLAN, South China Sea | Tags: arbitration, Central Party School, 王军敏, historic title, internal waters, Law of the Sea, nine dashed line, nine-dash line, Philippines vs China arbitration, PLA Daily, South China Sea arbitration, straight baselines, UNCLOS and South China Sea, Wang Junmin 8 Comments

The Central Party School’s article, headlined, “China does not accept the jurisprudential legitimacy of the SCS arbitral tribunal’s decision,” PLA Daily, July 18, p.6

One week on from the UNCLOS arbitration ruling on the South China Sea, the PRC’s response continues to somehow both clarify and complicate the issue at the same time. The latest episode in the unfolding mystery of the nine-dash line seems to diminish the line’s linkage with oil and gas claims designated unlawful by the Tribunal, while ramping up its associations with “historic title” over large sweeps of archipelagic waters [but seemingly not the entire Spratly archipelago – see update at the bottom].

On Monday an article published on p.6 of the PLA’s official newspaper offered a clear and detailed post-ruling definition of the nine-dash line from authors at the Central Party School. One of its main purposes was to refute the Tribunal’s inferred reading of the nine-dash line as a blanket claim to historic rights within the area it encloses. (Grateful HTs to Bill Bishop for digging it up and Bonnie Glaser for drawing attention to its significance.)

The article offers a more complex clarification of the line’s meaning than my optimistic reading of last week’s PRC Government Statement: whereas i read the Statement as implicitly separating the nine-dash line from China’s maritime rights claims, this article spells out at least some explicit links between the two.

On the other hand, it offers little or no support to the expansionist reading of the line that has underpinned many provocative PRC actions in recent years. In particular, the CPS scholars’ definition does not appear to support a claim to oil and gas resources out to the edge of the nine-dash line. This was a key element of the implied reading of the nine-dash line that the Tribunal struck down as unlawful. It’s a position that the PRC has backed up with coercion against other claimants’ energy survey ships in the past, and it’s also the basis for the notion, widespread in PRC domestic discourse, that rival claimants, especially Vietnam and Malaysia, are “plundering” China’s resources.

The writing of this article is attributed to CPS Postgraduate Studies Institute Deputy Dean Wang Junmin 王军敏, but the newspaper byline attributes it collectively to the CPS Center for Research on the Theoretical System of Socialism With Chinese Characteristics. It is, as such, not a government statement, but it’s very detailed, takes into account the Tribunal ruling, and could end up being close to the interpretation the PRC goes forward with in the wake of the ruling.

This interpretation can be summarized as follows. The nine-dash line is not a blanket claim to historic rights over all waters within, but rather to three distinct sets of rights across different geographical areas:

- Sovereignty over the islands within the line (the original meaning of the line when the KMT government published it in 1948)

- “Historic title” (历史性所有权) to waters enclosed by straight baselines drawn around island groups within the line (definitely including the Paracels, for which the baselines have already been announced, but not necessarily for the whole Spratly group)

- Non-exclusive fishing rights in others’ EEZs where (a) they overlap with the line and (b) Chinese fishers traditionally fished under high-seas freedoms

The article begins by arguing the UNCLOS does not constitute the entirety of international maritime law, and that customary international law continues to apply on matters where rules are not provided for in UNCLOS. In particular, the authors argue,

“The UNCLOS did not provide rules for the issue of territorial sea baselines for continental countries’ archipelagos; nor did it provide rules for historic rights, although it affirmed their status in international law.”

The author(s) state that the Philippines “distorted” the nine-dash line by (a) presenting it to the arbitral tribunal as representing a Chinese claim to sovereign rights and administration over all of the waters and seabed within; and (b) by arguing that the PRC claims “historic rights” (历史性权利) within the line, when in fact the PRC claims “historic title” (历史性所有权) over areas within the line, putting the case outside the Tribunal’s jurisdiction.

This line of argument appeared, fleetingly, in China’s 2014 Position Paper, which noted that disputes concerning “historic bays or titles” were exempt from compulsory dispute resolution under Article 298. According to the author(s), China has “historic title” to internal waters within archipelagic straight baselines.

So the authors say the Philippines “slandered” China’s nine-dash line by providing a distorted reading of its meaning to the Tribunal. Here’s how they explain its true meaning:

First, looking at China’s practical exercise of state power, China has never claimed all the waters within the line as its territorial sea or internal waters, exercising state sovereignty there. In fact, the 1958 Territorial Sea Declaration, at the same time as proclaiming the applicability of the straight baseline system and setting the breadth of China’s territorial seas at 12nm, implicitly noted that international waters [exist] between the Chinese mainland and coastal islands, and Taiwan and surrounding islands, Penghu, Pratas, Paracels, Zhongsha, Spratlys and other islands belonging to China [ZH]. In 1996 the Declaration of Territorial Sea Baselines announced the territorial sea basepoints and baselines for the Paracel Islands, thereby implying that within the ‘nine-dash line’ China would, in accordance with the UNCLOS, take the Paracels as an integrated whole entitled to territorial seas, contiguous zone, EEZ and continental shelf. Likewise, China’s 2011 note to the UN Secretary General claimed that the Spratlys also enjoy territorial seas, EEZ and continental shelf. This implies: China has never claimed all the waters within the ‘nine-dash line’ as China’s historic waters or that it enjoys historic rights .

Second, the Philippines used the Chinese expression ‘historic rights’ (历史性权利) to argue China had not claimed ‘historic title’ (历史性所有权). As everyone knows, historic rights in international law refers to the rights enjoyed continuously by a state in certain waters since ancient times. Historic rights include historic title and non-exclusive historic rights. Waters subject to historic title are called ‘historic waters’ (历史性水域), these are part of a coastal state’s internal waters or territorial seas, and mainly include historic bays. other coastal waters adjacent to the coast, and the waters within archipelagos. Non-exclusive historic rights are divided into historic rights of passage and historic fishing rights. The former refers to innocent passage through internal waters, specifically all countries’ rights of innocent passage through areas not originally regarded as internal waters, but which became enclosed as such through the coastal state’s application of straight baselines.[ZH] The latter refers to non-exclusive rights to fish in areas that were previously fished in accordance with high seas freedoms but which have now become a coastal state’s EEZ [or] archipelagic waters.[ZH] The mere use of ‘historic rights’ in the PRC EEZ and Continental Shelf Law, by MFA spokespersons, and by Chinese scholars, does not imply China does not claim ‘historic title’. In fact, our country has historic title and historic fishing rights in different areas within the nine-dash line.

Third, China’s ‘nine-dash line’ rights claims mainly comprise: 1. China has territorial sovereignty over islands, reefs, cays and shoals within the line; 2. China has historic title to waters within archipelagos or island groups that are at relatively close distance and that can be viewed as an integrated whole, these areas are China’s historic waters, they are our country’s internal waters,[ZH] and China has the right to draw straight baselines around the outermost points of these waters and claim state administrative zones such as territorial seas, EEZs and continental shelves etc. in accordance with the UNCLOS. 3. When waters within the ‘nine-dash line’ become [part of] another country’s EEZ or an archipelagic state’s waters, China has the right to claim historic fishing rights or traditional fishing rights in the overlapping areas.

The many references to non-exclusive fishing rights contrast sharply with the complete absence of any mention of claims to oil and gas rights. As noted, it was precisely that (implied) claim that led to the line being designated unlawful. The 2012 CNOOC oil blocks, especially, convinced the Tribunal that China was acting in accordance with this reading of the line (see especially the Award paragraphs 208-214). But under the above definition, the nine-dash line seems to have no significance at all to the geographic scope of China’s energy rights claims.

The other striking thing about this definition is the heavy focus on the issue of historic title over internal waters enclosed within straight baselines around island groups — an issue addressed in an excellent article by Yanmei Xie over the weekend. There is plenty of reason to think that straight baselines might be about to enclose the Spratlys, a move that would significantly harden the PRC’s position.

But there might be yet another strange twist here. Looking again at the third paragraph above, the Party School authors define China’s claim of historic title to internal waters as existing in “archipelagos or island groups that are at a relatively close distance and that can be viewed as an integrated whole (my emphasis).” Which kinda seems to suggest the historic title aspect might be referring to the Paracels but not the Spratlys.

I’ve heard the “can be viewed as an integrated whole” argument for archipelagic straight baselines in the South China Sea numerous times from PRC sources, but i’ve never come across the “at a relatively close distance” criterion before. Why else might they have included this?

Here’s the answer (update 21/7):

Dylan Jones points out that the relatively close distance criteria refers to the distances between the islands, and a careful re-reading of the article confirms this. Here’s the Central Party School authors’ detailed explanation in translation:

“Most international legal experts consider state practice is forming, or has already established, international legal norms regarding continental states’ offshore archipelagos: the straight baseline system’s applicability to continental states’ offshore archipelagos is restricted to those archipelagos that can be seen as an integrated whole, with relatively small distances between the islands, and intimate connections between the waters and the mainland [. . . ]

“The most likely and most appropriate method for China’s territorial sea baselines in the Spratly Islands is to imitate the method used in the Diaoyu Islands, for example, taking the main islands and reefs such as Itu Aba, Pagasa, West York, Spratly and Mischief as the centre, and linking together the surrounding reefs to establish baselines [. . .]”

“Looking at historic rights, China has historic title to waters between the relatively close, intimately connected islands that qualitatively comprise a unified whole, these waters are historic waters, China’s internal waters . . . China has the right to take those groups of islands within the Spratlys that are relatively close to each other as a single entity to establish territorial sea baselines,[ZH] and China’s Spratly Islands in the SCS have maritime administrative zones such as territorial seas, EEZ and continental shelf.”

So the author(s) do in fact believe a “historic title” claim over “internal waters” enclosed by straight baselines exists in the Spratlys — but rather than covering the entire archipelago, as per the Paracels baselines in 1996, it would only cover those parts within the archipelago that are close together. Here’s the Diaoyu example they refer to:

Diaoyu Islands straight baselines submitted to the UN in 2012

The authors repeat this “within the Spratlys” + “close together” + “intimately connected” recipe for Spratly straight baselines (and thus the scope of internal waters subject to historic title) no less than 6 times, so it’s fair to conclude this was a point they were keen to get across. That would be a tough sell domestically given that it would probably exclude James Shoal, that shallow patch of ocean considered by many (probably most) Chinese people to be the southernmost point of the nation’s sacred territory. This would be one reason to think the party might not make a Spratly baseline declaration in the near future after all.

Another rambling post…i really ought to shut up and let things run their course. But the riddle of the nine-dash line continues to string me along rather compulsively. If any readers have made it this far then at least i mustn’t be the only one.

Did China just clarify the nine-dash line?

Posted: July 12, 2016 Filed under: South China Sea | Tags: historic rights, nine dashed line, nine-dash line, Philippines vs China arbitration, South China Sea arbitration, UNCLOS, UNCLOS and South China Sea 5 Comments

Locations of China’s 2011-2012 coercive operations against foreign energy surveys. As far as i’m aware, no similar incidents have been reported in these areas since that time. Also shown in green is the maximum EEZ area the PRC might have claimed in the SCS under UNCLOS before the arbitral tribunal ruled that there are no proper islands in the Spratly archipelago. This reduced China’s maximum legal claim under UNCLOS to the sprinkling of 24 nautical mile-wide circles roughly indicated on the map. (Compiled using Google Earth, incident coordinates found in official materials, and Greg Poling’s CSIS report.)

I’m going to make this very quick because i should get back to reading a 501-page piece-by-piece dismantling of maybe 95% of China’s maritime claim south of the Paracels.

Unless i’m mistaken (again), i think the official Statement of the Government of the People’s Republic of China in response to the arbitration result might just have made an important and long-awaited clarification of the meaning of the nine-dash line.

The status of a PRC Government Statement is about as high as a statement’s status can get in the the PRC system. This one contains five numbered points, each explaining a different aspect of the PRC’s position.

- China’s historical claim to territorial sovereignty and “relevant rights and interests” over islands in the SCS

- The PRC government’s actions to uphold said sovereign rights and interests since 1949

- Four elements of the PRC’s rights and interests in the SCS:

- Sovereignty over SCS islands,

- Internal waters, territorial seas & contiguous zones based on SCS islands

- EEZ & Continental Shelf based on SCS islands

- Historic rights

- China’s opposition to other countries’ occupation of some of the Spratly archipelago

- China’s commitment to freedom of navigation for international shipping

I’m pretty sure this is the most comprehensive encapsulation of China’s claims in the South China Sea ever made. None of the elements are new, but i don’t think they’ve all appeared side-by-side in one document before. The claim to “historic rights”, for example, is included in the PRC’s 1998 EEZ & Continental Shelf law, but that document doesn’t refer to the nine-dash line. A diplomatic note to the UN in 2009 included the nine-dash line map for the first time officially, but didn’t mention historic rights. And another 2011 note to the UN specified that the Spratlys were entitled to EEZ and Continental Shelf, but didn’t include the nine-dash line map or “historic rights”.

Of particular note is the Statement’s treatment of the nine-dash line. The first paragraph of point 1 begins by referring to its sovereignty over the territories of the Spratlys, Paracels, etc., states that China’s activities there date back 2,000 years, and then concludes that this established “territorial sovereignty and relevant rights and interests.” What’s especially interesting is that an explanation of the nine-dash line is presented separately in a second paragraph (also under point 1) that reads:

“Following the end of the Second World War, China recovered and resumed the exercise of sovereignty over Nanhai Zhudao which had been illegally occupied by Japan during its war of aggression against China. To strengthen the administration over Nanhai Zhudao, the Chinese government in 1947 reviewed and updated the geographical names of Nanhai Zhudao, compiled Nan Hai Zhu Dao Di Li Zhi Lue (A Brief Account of the Geography of the South China Sea Islands), and drew Nan Hai Zhu Dao Wei Zhi Tu (Location Map of the South China Sea Islands) on which the dotted line is marked. This map was officially published and made known to the world by the Chinese government in February 1948.”

The nine-dash line, according to this authoritative statement, was created to “to strengthen the administration over” the Chinese-claimed islands of the South China Sea. No mention of “historic rights.”

The omission of a link between the nine-dash line and China’s “historic rights” wouldn’t, on its own, mean much, if they weren’t mentioned elsewhere in the statement. But they are: they are on the list of 4 elements that comprise the PRC’s maritime claims, where they are once again listed separately from the territorial claims represented by the nine-dash line.

This seems to imply very strongly that the nine-dash denotes the extent of the area within which China claims sovereignty over islands, and does not demarcate the extent of the area within which China maintains a claim to “historic rights,” which had been one of the most likely readings.

The separate treatment of the nine-dash line strongly implies that the nine-dash line does not depict the geographical extent of the PRC maritime rights claim.

If this implication was intended, it should be apparent in China’s behaviour. One sign in favour of this reading is that the PRC’s “cable-cutting” operations against Vietnamese survey ships around the edge of the nine-dash line area in 2011 and 2012 seem to have ceased since that time (see above map).

Going forward, if this is correct, we might also expect to see a winding back of China’s opposition to other countries’ activities near the edges of the nine-dash line, such as Vietnam’s oil and gas projects in the Nam Con Son Basin. And the path of the PRC Coast Guard’s “regular rights defense patrols” should no longer hug the nine-dash line. Where fishing in the “traditional fishing grounds” off the Natuna Islands (mostly outside the nine-dash line) might fit in, i’ve no idea.

And with the nine-dash line appearing decoupled from “historic rights” in a Statement of the PRC Government, this should mandate the same treatment to be repeated in future statements by lower-level authorities like individual leaders, the MFA and its spokespersons.

Time to get back to work, long and fascinating night ahead….please share any thoughts and corrections. I can only hope my hasty read of this present statement might turn out a little closer to the mark than my prediction of the arbitration outcome.

China’s latest oil rig move: not a crisis, and maybe an opportunity?

Posted: June 27, 2015 Filed under: China-Vietnam, South China Sea, Western media | Tags: China-Vietnam, China-Vietnam relations, Chinese foreign policy, HYSY-981, Nam Con Son, Nam Con Son Basin, nine dashed line, oil and gas, south china sea, straight baselines 1 Comment

Location of Chinese drilling rig HYSY-981, with approximate equidistant lines between Hainan, the Vietnamese coast, and the disputed Paracel Islands (map by Greg Poling)

On June 25, China’s Maritime Safety Administration announced the gargantuan drilling rig HYSY-981 had returned to the South China Sea for more drilling operations, raising concerns of a return of the serious on-water clashes last year.

Here we go again was a widespread sentiment on Twitter. The apparent expectations of impending repeat showdown appear to result in part from the headline of a widely-shared Reuters story, ‘China moves controversial oil rig back towards Vietnam coast‘. This might be technically correct (i’m not sure exactly where the rig was before) but this year’s situation is quite different to last year’s.

Serious on-water confrontation is unlikely this time around because the rig is positioned in a much less controversial area. It is a similar distance from the Vietnamese coast (~110nm) but much further from the disputed Paracel Islands (~85nm), and much closer to the undisputed Chinese territory of Hainan (~70nm, compared to more than 185nm in 2014).

As explained below, the parallels between this area and others where China has objected — sometimes by coercive means — to Vietnamese oil and gas activities, make the latest move a good opportunity to grasp an important aspect of the PRC’s position in these disputes, and pin down some of its inconsistencies.

“Hello, Sansha”: Cheng Gang returns, brandishes Vietnam’s name . . . and lies

Posted: August 13, 2012 Filed under: CMS (China Maritime Surveillance), CNS, FLEC & Ministry of Agriculture, Global Times | Tags: Beijing Youth Daily, Cheng Gang, Chinese journalists, Communist Youth League, 程刚, Global Times, Huanqiu Shibao, nine dashed line, Sansha, south china sea, Yongxing, Yuzheng-306, 永兴岛, 三沙 1 Comment

‘Hello, Sansha’ – graphic accompanying Beijing Youth Daily report on a July 2 visit to Woody Island 永兴岛. (Note superimposed nine-dash line.)

I knew it was incident season but I went anyway. A mistake i have learned from: from this point onward, until the disputes are resolved or my thesis is finished, i vow never to take a holiday in July, unless the destination is the South China Sea. Ten days after my return, i’ve only just finished properly studying all the recent action. The next few posts will sketch out in basic chronological order, recent developments as seen through the PRC’s major internet news media.

The establishment of Sansha City looms large. According to a keyword study of 15 major Chinese newspapers, it was in the top five most-mentioned domestic politics-related terms in the first 6 months of 2012 — a (suspiciously) remarkable achievement, given that its creation was only announced on June 21. There is no doubt, however, that Sansha has been very heavily covered in China’s state-controlled media since its announcement. The extent to which it has “attracted” this attention or had this attention ordered towards it is, of course, hard to say — the answer is clearly both, but in what proportions?

The flurry of first-hand accounts of visits by reporters began well before the opening ceremony on June 24. Beijing Youth Daily reporter Li Chen 李晨 visited on July 2, filing a story that ran on July 9 under the headline, ‘Hello, Sansha’. (The story was made available in English by the China Daily but the translation has since been taken down. It remains online here.) This was accompanied by the graphic above, with the nine-dashed line superimposed. It began:

Would you be surprised if I told you there was a city with an area equivalent to one quarter of China’s territory?

The graphic and the opening line show that the view of the nine-dashed line as representing China’s territorial waters, far beyond the officially-stated claim to the islands within, continues to be propagated through the official media. The apparent lack of desire to educate the Chinese public on the limits of China’s claims in the South China Sea suggests that the government sees nationalistic public opinion on the issue as more of a weapon than a threat.

Li Chen’s report also ran prominently in the July 15 edition of the Shanxi Evening News, but there were numerous other accounts of visits to Sansha around that time. Notable among them was this ‘Exclusive visit to South Sea frontline Sansha’ from the intrepid Cheng Gang 程刚 of the Huanqiu Shibao, who wrote that he was making his fifth visit to Woody Island/Yongxing 永兴岛. Some of Cheng’s reporting was made into an English-language article for the Global Times, but many of the interesting details have been left out.

“Ours before, still today, more so in the future”: who is claiming the whole South China Sea…and why?

Posted: March 8, 2012 Filed under: China-Philippines, China-Vietnam, Comment threads, Global Times, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, PRC News Portals, State media, Weibo | Tags: 9-dash line, china maritime dispute, Chinese media, Hong Lei, MFA, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, nine dashed line, paracel islands, south china sea, spratly islands, u-shaped line, 洪磊 4 Comments

China’s official nine-dashed line, as attached to numerous documents submitted to the UN. China claims the islands within the 9-dashed line, not the whole maritime area contained within.

Foreign Ministry spokesman Hong Lei has attracted some heat from the hot heads of China’s internet population, for daring to state [zh] that “no country, including China, has laid claim to the entire South China Sea”.

Apparently seizing upon this domestic criticism of Hong Lei, the Global Times’ English edition has published a piece positing that “public will” is increasingly influencing foreign policy on the sea disputes. While Vietnam and the Philippines have tried to “woo the public” with hawkish stances,

China uses less public will to press other countries and does not seek to present a hard stance to win people over, despite paying the price of occasional fierce criticism.

On the South China Sea issue, I think China’s claims are misunderstood by media employees, many alleged experts and, perhaps most significantly, ordinary people inside China. While opinion-page pundits like Pan Guoping may claim the entire sea for China, and international media can sneer at the outrageous ambiguity of the famous nine-dash line, the PRC’s claim has actually been quite clear for some years. As expressed ad nauseum in official statements and UN submissions over the past few years,

China has indisputable sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea and the adjacent waters

The islands . . . and the adjacent waters. China, pretty unambiguously, does not claim the whole South China Sea, and the attachment of the above map to diplomatic notes to the UN in 2009 and 2011 indicates further that the nine-dash line does not depict China’s claimed maritime boundaries. The BBC misrepresents the PRC’s position in every report it makes on the South China Sea, to which it attaches this map:

“You cannot not support this”: the passport saga impresses China’s online nationalists

Posted: November 27, 2012 | Author: Andrew Chubb | Filed under: Academic debates, China's foreign relations, China-India, China-Philippines, China-Vietnam, Comment threads, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, PRC News Portals | Tags: Arunachal Pradesh, Chinese foreign policy, Chinese nationalism, Foreign Ministry, foreign policy incoherence, Hua Chunying, maps, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Public Security, new Chinese passports, new foreign policy actors, nine dashed line, online nationalism, passports, PRC foreign policy | 3 CommentsNew PRC e-passport and old version

Students of PRC foreign policy constantly come up against the question of whether the actions of the Chinese state are the result of decisions made by the centralised leadership or individual state agencies.

Linda Jakobson and Dean Knox’s 2010 SIPRI report, ‘New Foreign Policy Actors in China‘ provided an excellent overview of the range of players on the Chinese foreign policy scene. Taking a similar approach in relation to the South China Sea issue, the International Crisis Group’s ‘Stirring up the Sea (I)‘ report earlier this year emphasised the incoherence that can result from individual (and sometimes competing) agencies acting according to their own priorities rather than a consistent centralized policy.

In the PRC’s latest diplomatic disaster, images embedded on the visa pages of the PRC’s new passports have managed to simultaneously provoke the official ire of Vietnam, the Philippines, India and Taiwan.

Close-up of nine-dash line depiction in new People’s Republic of China passport

The two South China Sea claimants have protested the inclusion of a map including the nine-dash line representing China’s “territory” in the disputed sea, India disputes the maps’ depiction of Arunachal Pradesh as part of Tibet, and the passports’ pictures of Taiwan landmarks prompted rare expressions of anger from Ma Ying-jeou and the ROC’s Mainland Affairs Council.

This looks to be a classic case of policy uncoordination resulting from a domestically-focused agency taking actions that directly impinge on other countries’ interests. From the FT’s report breaking the story:

The next day the Guardian quoted MFA spokeswoman Hua Chunying saying, “The outline map of China on the passport is not directed against any particular country.” Yet neither the Chinese nor the English versions of the official transcript of Hua’s November 23 press conference include the comment, suggesting that the Foreign Ministry remained disinclined to take responsibility for the move.

The SIPRI and ICG reports mentioned above didn’t focus much attention on the Ministry of Public Security as a player in PRC foreign policy, but it has certainly become one, inadvertently or otherwise.

Read the rest of this entry »