China’s latest oil rig move: not a crisis, and maybe an opportunity?

Posted: June 27, 2015 Filed under: China-Vietnam, South China Sea, Western media | Tags: China-Vietnam, China-Vietnam relations, Chinese foreign policy, HYSY-981, Nam Con Son, Nam Con Son Basin, nine dashed line, oil and gas, south china sea, straight baselines 1 Comment

Location of Chinese drilling rig HYSY-981, with approximate equidistant lines between Hainan, the Vietnamese coast, and the disputed Paracel Islands (map by Greg Poling)

On June 25, China’s Maritime Safety Administration announced the gargantuan drilling rig HYSY-981 had returned to the South China Sea for more drilling operations, raising concerns of a return of the serious on-water clashes last year.

Here we go again was a widespread sentiment on Twitter. The apparent expectations of impending repeat showdown appear to result in part from the headline of a widely-shared Reuters story, ‘China moves controversial oil rig back towards Vietnam coast‘. This might be technically correct (i’m not sure exactly where the rig was before) but this year’s situation is quite different to last year’s.

Serious on-water confrontation is unlikely this time around because the rig is positioned in a much less controversial area. It is a similar distance from the Vietnamese coast (~110nm) but much further from the disputed Paracel Islands (~85nm), and much closer to the undisputed Chinese territory of Hainan (~70nm, compared to more than 185nm in 2014).

As explained below, the parallels between this area and others where China has objected — sometimes by coercive means — to Vietnamese oil and gas activities, make the latest move a good opportunity to grasp an important aspect of the PRC’s position in these disputes, and pin down some of its inconsistencies.

Approximate distances of Chinese HYSY-981 drilling operations in June 2015. My calculations using Google Earth give the slightly different distances specified below (source: @SCS_news)

.

The Vietnamese response

At the time of writing, June 28, the Vietnamese Government had not officially commented, but Vietnamese state media have quoted the former head of Vietnam’s Border Committee Dr Tran Cong Truc as stating it is in an area of overlapping EEZ claims (HT @SCS_news). This is because it is less than 200nm from the Vietnamese coast, from the coast of China’s Hainan Island, and also from the disputed Paracel Islands. Vietnamese Petroleum Association chairman Ngo Thuong San last year argued these areas should be off-limits for development until demarcation is complete:

According to international law, no party is entitled to conduct unilateral oil and gas exploration and extraction activities in the overlapping areas that have yet to be delimited.

More specifically, in a later English-language report, Dr Tran said China’s move violated a Sino-Vietnamese agreement to negotiate maritime jurisdictional boundaries south of the Gulf of Tonkin:

“When the said negotiation has yet to come any agreement, no parties involved can take any unilateral action in this the overlapping area,” the ex-official stressed. If a party wants to conduct any activity in the overlapping area, both parties may agree to a temporary solution for such activity, Truc said. He added that Vietnam has suggested a negotiation on this issue with China, but China ignored it.

Last year, Vietnam mounted sustained opposition to the HYSY-981’s operations using a combination of fishing boats, driftwood, constant on-scene media coverage from local and international journalists, and official pressure through the United Nations. This time around, however, the geographical position would make it harder for Vietnam to rally world public opinion to its cause, and more difficult to mount a credible challenge on the water.

Remembering that few if any foreign countries take a position on the disputed islands, the relative proximity of the area to the Chinese coast makes the PRC’s activities naturally less likely to appear preposterous to outsiders. It also makes it easier for the PRC to defend this operation on the water, since it’s closer to the home ports of its navy and Coast Guard forces. Vietnam, in short, would have little to gain from physically disrupting PRC operations here.

.

A mirror image

What China’s latest move does offer Vietnam, however, is an opportunity to highlight real inconsistencies in the PRC position in the South China Sea. Because if Vietnam’s oil and gas projects in the southern part of the South China Sea are in disputed waters, as the PRC has repeatedly claimed, then so too is the current project.

The Nam Con Son Basin, more than 500nm to the south, is the site of some of Vietnam’s most productive oil and gas fields. Energy companies from countries including the US, UK, Korea, Japan, Australia, India, Germany and Russia have helped Vietnam develop the fields over the past two decades. But it’s partially within the nine-dash line, and China has officially laid claim to this area via a succession of diplomatic protests (see a list of them here). From 2006 onwards, as documented in Wikileaks cables and Bill Hayton’s book, the PRC pressured many of the companies involved to pull out, in some cases warning they were committing “grave violations” of China’s “indisputable sovereignty” in the area.

The area is in many ways a mirror image of the area China has positioned HYSY-981 in. Both are within 200nm of a disputed island, but also within 200nm of an undisputed coast. As the map below illustrates, they are also both on the coastal state’s side of a theoretical median line. The yellow markers below indicate the approximate locations of Vietnamese oil and gas initiatives that China has protested since 2006. The white lines are median lines between the relevant coastlines and offshore land features, as calculated by Greg Poling in his 2013 CSIS report The South China Sea in Focus.

Nam Con Son Basin, with yellow markers indicating Vietnamese energy projects officially opposed by China (adapted by Andrew Chubb from CSIS GIS file available here)

Of course, China would justifiably point out that the median line above was calculated using expansive Vietnamese coastal baselines (the red lines) that are not recognized by many countries — including the US — due to the “excessive” amount of territorial waters they enclose. But even if we rudely scale back Vietnam’s baselines to a more restricted position, the oil and gas projects China has objected to remain on the Vietnamese side of the theoretical equidistant line.

Vietnamese energy projects in Nam Con Son basin protested by China, with approximate equidistant line calculated using less expansive Vietnamese baselines (adapted by Andrew Chubb from CSIS GIS file)

So in the northern part of the South China Sea, we have Vietnam claiming overlapping jurisdiction in areas that are closer to the Chinese coast than to the disputed Paracel Islands, the closest of which is in any case occupied by China. Meanwhile, in the southern part of the South China Sea, China is disputing areas that are closer to the Vietnamese coast than to the disputed Spratly Islands, the closest of which is in any case occupied by Vietnam.

Both areas are de facto disputed, but in both cases the grounds for dispute are shaky. The best that could be said for either is that at least the Vietnamese claim of overlapping jurisdiction in HYSY-981’s current vicinity concerns an area that’s within 200nm of Vietnam’s coast, rather than stemming solely from islands that are themselves in dispute. For this reason, it looks advantageous for Vietnam to have the issue of median lines and energy development on the agenda of discussions regarding the South China Sea.

.

A moment of (relative) clarity?

China’s drilling operation in the northern part of the South China Sea could be interpreted as a kind of implied clarification of its position, namely, that energy development in a disputed area on the coastal state’s side of a theoretical median line is acceptable.

Obviously i’m not privy to the arguments the Vietnamese side might be making in its negotiations with China, but it seems to me that they could, if they wanted to, publicly call out the obvious inconsistency between China’s latest HYSY-981 move and the PRC’s longstanding objections to the energy developments in the Nam Con Son basin and elsewhere on the Vietnamese side of the median line. This would give China a much-needed incentive to take the maritime demarcation negotiations seriously (according to some sources, including Chinese government materials, many in the PRC perceive slowing the progress of these negotiations down to be advantageous).

It would also be another good reason for China to continue steering clear of the kinds of dangerous coercive actions seen in 2011 and 2012, when PRC ships cut the cables of several Vietnamese seismic survey ships.

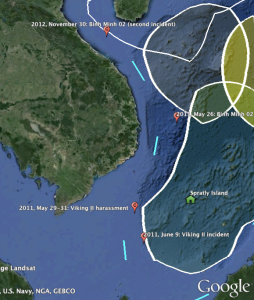

2011 & 2012 Sino-Vietnamese “cable-cutting” incidents (other unreported incidents may have occurred)

All told, using this issue to challenge China to be consistent on the issue of median lines could potentially help clarify one aspect of the enormously complex South China Sea situation. A follow-on question is whether such clarification would be more likely to contribute to the easing of tensions, or a hardening of positions?

I tend to think if China is prompted to expressly state the principle upon which its rights to operate in the area in which HYSY-981 is now stationed are based, it should logically be less inclined to forcefully oppose other countries’ analogous being carried out under the same principle. But as always, please do share any responses, thoughts, or guffaws of derision via the comments section below or any other contact method.

[…] near the edges of the nine-dash line, such as Vietnam’s oil and gas projects in the Nam Con Son Basin. And the path of the PRC Coast Guard’s “regular rights defense patrols” should no […]